Ahmad marked the 80th day since his evacuation from Kabul on Saturday.

He adds to the number each morning that he wakes up on a thin mattress in a second floor bedroom at an Abu Dhabi humanitarian camp, with no indication of how many more days he’ll count.

Ahmad made it out of Afghanistan on Aug. 25 on a Kam Air flight — the airline that employed him for more than ten years — in the final days of the United States-led evacuation.

He put on his bright, orange-accented uniform that chaotic summer week and pushed through crowds outside Hamid Karzai International Airport because the airline was tasked to help with evacuations. He only made it through the airport gates because a Taliban member checked his ID against a list of employees, suddenly putting him on the group’s radar.

“It was a must for me to come to the airport and do my job [so] the pilots could perform,” he told Spectrum News in a phone interview from Emirates Humanitarian City, where he’s been for the last two-and-half months.

“Everyone did their part.”

Ahmad said that because the Taliban could identify them, he and his coworkers made the decision to evacuate on one of the last Kam Air flights out of Kabul.

“I was on duty with nothing except less than $100 with me,” he said. “At that time, we didn't know we will get stuck in here for this long.”

Unlike the approximate 74,000 Afghan nationals who have made it to the U.S. since the August evacuation, Ahmad and thousands of others are in limbo in Abu Dhabi, at a temporary camp voluntarily paid for and run by the United Arab Emirates government.

The State Department has applied a different standard to Afghans who were flown out of Kabul on non-U.S. military aircraft in August — even as they were counted in the daily, public totals cited by government officials and evacuated under U.S. supervision — leaving them without a clear path to resuming their lives. Most do not have clear justification for a U.S. visa, making their fate more complicated.

There are between 10,000 and 12,000 people living at the Emirates Humanitarian City, a volunteer working at the camp estimated for Spectrum News, though at least a few thousand arrived after August on intermittent charter flights out of Afghanistan. The State Department has not publicly released totals from the camp.

At least 5,000 have moved on to the U.S. already, according to numbers provided by an official as of Oct. 26.

Afghan evacuees in the UAE who spoke to Spectrum News said the conditions in the facility are quite good — the food, supplies for families, like diapers, and access to a clinic and mosque. Volunteers, staff and Emirati representatives check in and try to make regular improvements with their feedback.

)

Their complaint, rather, is the dearth of information from U.S. officials about when things will change.

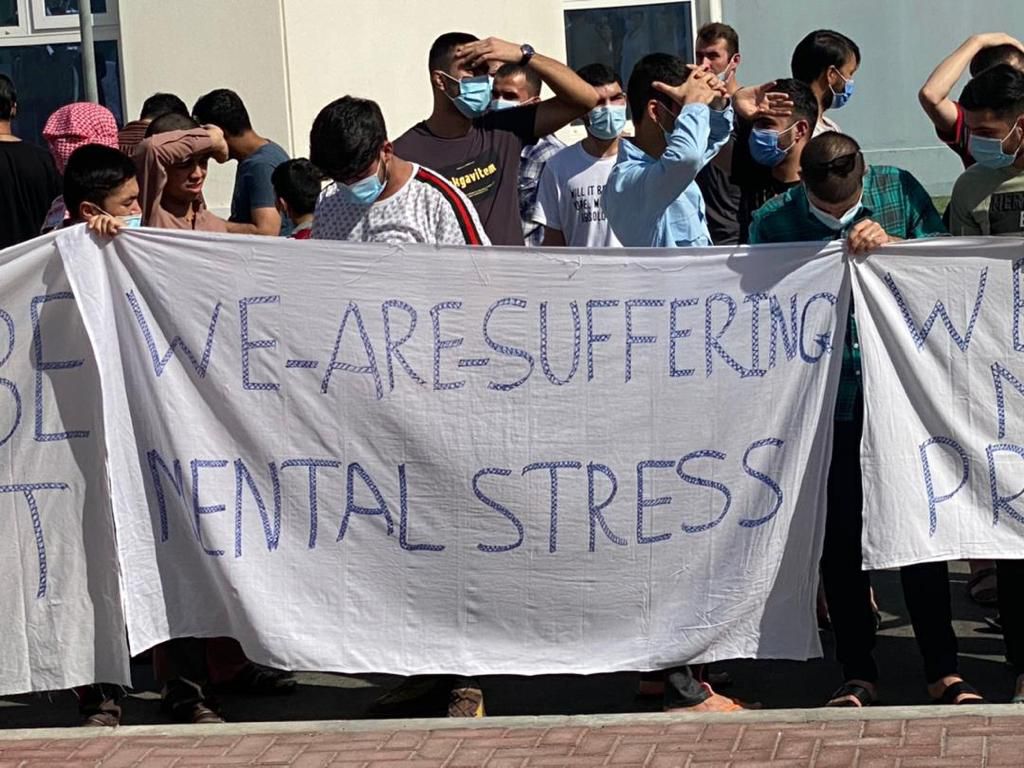

On Friday afternoon, a few dozen Afghans gathered in the courtyard at the Abu Dhabi camp to protest their indefinite stay.

“We are not prisoners,” read one sign written on a bedsheet with blue marker.

“We are suffering mental stress,” read another.

“Secretary Anthony Blinken [sic] — your department has forgotten ten-thousands of vulnerable and at-risk Afghan in UAE, which are left in limbo,” said another sheet held by a group of men.

Small children and families living in the camp also joined the demonstration.

Despite the protest, officials have few concrete answers.

“We are working in tandem with our UAE partners to conduct comprehensive screening of evacuees for onward travel,” a State Department spokesperson told Spectrum News. “This is a round-the-clock operation that requires close coordination between multiple U.S. government agencies and their UAE counterparts.”

One Iraq War veteran first flew to Afghanistan in late August to help a group of his friends, thinking he’d volunteer with the U.S. evacuation for a few weeks as the group tried to rescue Afghan interpreters they’d worked with in combat.

Now, he’s been living in Abu Dhabi for more than two months, conducting thousands of initial interviews at the Emirates Humanitarian City with a small patchwork of staff and volunteers: two other veterans and a handful of Afghan evacuees who offered to translate.

“Right now, we're down to about three people. We don't have the size or staff able to do this,” he said. “This became a far greater humanitarian effort than was originally planned.”

The volunteer’s gig soon became a full-time job. He spoke to Spectrum News on the condition of anonymity, since he was not authorized to discuss his work in the UAE. He was contracted by a support services firm called Raven Group International that has previously partnered with the U.S. government.

He struggles with the most common question evacuees have: When will I leave?

“Why they don't have an answer is because we're not State Department,” he told Spectrum News. “We can't give them a clear answer.”

For now, the Raven Group team passes Afghan names to U.S. officials after their interviews, and he helps build an information packet for each person.

Some Afghans at the Emirates Humanitarian City have a clear pathway to the United States — they’re a legal permanent resident or a former interpreter for the U.S. military; others might qualify for humanitarian parole, such as single women — but people like Ahmad and his Kam Air colleagues don’t have an obvious claim.

Yet both advocates and staff who spoke to Spectrum News point out that many of them were all evacuated together in August as part of the same, tumultuous American operation.

White House press secretary Jen Psaki gave regular updates at the time that highlighted people flown out on non-American planes: "19,000 people were evacuated from Kabul over a period of 24 hours," she said on Aug. 25.

"This is the result of 42 U.S. military flights which carried approximately 11,200 evacuees, and 48 coalition flights which carried 7,800 people, for a total of 90 flights out of Kabul."

“The only reason they got loaded on the aircraft is because of the way the U.S. government handled the extraction,” the Raven Group contractor said. “I wish State Department was more helpful. If anyone can figure out what button to push, it'd be great.”

State Department officials said one challenge at the UAE camp is that the population also includes Afghans evacuated on privately-sponsored charter flights, some who have no valid reason for U.S. entry.

“This puts the individual travelers at risk with no plan for relocation to the United States; damages the bilateral relationship of the United States with the destination countries; and makes it more difficult for the U.S. government to rely on those partner countries,” a spokesperson said.

But for those who arrived amid the August chaos, like Masoud — a different Kam Air employee who worked on the cabin crew — they wonder less about where they will go and more about when they will reconnect with their family back in Afghanistan or elsewhere.

“I have three kids — my wife, my brothers, my parents, they’re in Kabul,” he told Spectrum News. “I was the only one taking care of my family. Thousands of people like me have the same problem.”

“We are living here like prisoners,” he added. “The only thing that people hear is ‘Be patient. Be patient and everyone will go.’"

For the first 73 days in the camp, Masoud, Ahmad and the other single males only saw sunlight through their bedroom windows, solely allowed outside in the early morning and late evening hours and always in the dark.

The restrictions were part of the UAE government’s effort to prioritize safety and keep single females and males separate, the Raven Group employee explained. Families were allowed outside during daylight hours, and the men’s blocks were allowed as of Nov. 6.

Still, those protocols were only designed to last a few weeks, after which Afghan evacuees were meant to transition on to the U.S. or other countries who might resettle them. The Emirates Humanitarian City was initially built in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic to house people who came from Wuhan, China.

Most Afghan evacuees flown to third countries were initially delayed in reaching the U.S. because of a sudden measles vaccination campaign and three-week quarantine. But then at other locations, like American military bases in Germany and elsewhere, flights resumed rapidly.

Evacuees in the UAE camp who spoke to Spectrum News were appreciative of the effort to make the facility comfortable. Humanitarian groups are on the ground, including the Red Crescent and NCEMA, the UAE government’s emergency management agency.

It’s their mental state — and lack of communication from U.S. officials — that weighs on them.

“Some of our colleagues got depression here. Two, three times, panic attacks. Even the worst case scenario, I heard three people left back to Afghanistan,” Ahmad said. “Now they are in hiding [from the Taliban]. They said it's better to be hiding in our homes rather than to stay here.”

A State Department spokesperson reiterated that they are working to process people both quickly and with security vetting in mind. They did not provide the number of staff working at the UAE camp or an expected timeline.

But they said the Department of Homeland Security in recent weeks has deployed about 300 personnel to screen Afghan evacuees who are scattered across the globe at lilypad locations in Bahrain, Germany, Kuwait, Italy, Qatar, Spain and the United Arab Emirates.

Advocates say the Biden administration has a responsibility to the people in limbo in third countries, just as they did to the people who happened to leave Kabul on a military C-17.

“We have an obligation to make sure that they have permanent protection, honestly, somewhere. And ideally, that'd be in the U.S.,” said Sunil Varghese, policy director at the International Refugee Assistance Project (IRAP).

IRAP and two other human rights organizations released a report this week calling for a coordinated, American effort to create pathways to protection for vulnerable Afghans stuck in third countries and Afghanistan.

Another factor at play: The public criticism the Biden administration has already faced for evacuating Afghans who do not have a direct connection to the U.S., while leaving the majority of interpreters and other American allies behind.

Ahmad will count day 81 on Sunday. He writes down any news of progress on the Notes app of his iPhone.

“I’m trying my best to stay on top of things. But day by day, when you get up from sleep, you have nothing to do,” Ahmad said. “I was used to the same routine for ten-and-a-half years.”

“But here? Just eat and sleep.”