Tom Daschle knows a thing or two about bipartisanship.

The longtime former lawmaker served as senator from South Dakota beginning in 1987, and the typically red state continued to re-elect the Democrat in each election until 2004. Daschle was — for a brief, two-week period — Majority Leader during an evenly divided, 50-50 split Senate in January 2001, and again from June 2001 - January 2003.

There are echoes of Daschle’s experience in today’s Congress: Democrats hold a small 220-212 majority in the House of Representatives, and Vice President Kamala Harris offers the tie-breaking vote for Democrats in the Senate.

It has proved difficult for Democrats to pass key components of President Joe Biden’s agenda with a slim hold on Congress.

For weeks, Democrats and Republicans have debated two central bills. One is a $1.2 trillion bipartisan infrastructure package, which passed the U.S. Senate in August. Another, related proposal is a $3.5 trillion spending bill to expand the social safety net and address climate change.

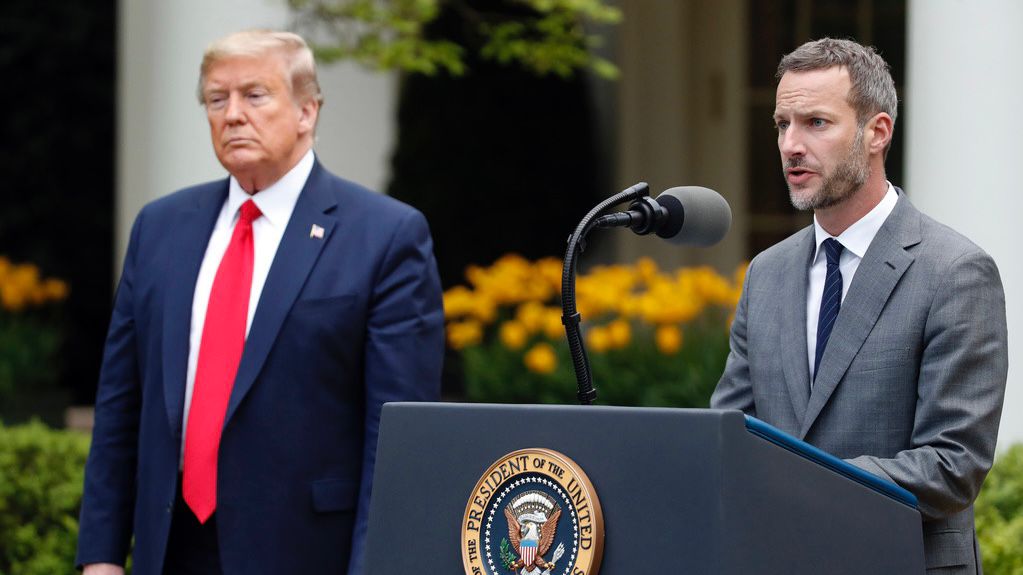

Spectrum News Chief National Political Reporter Josh Robin sat down with Daschle, who had some words of advice for both parties.

“I think all members of Congress just need to recognize that compromise is the oxygen of democracy,” Daschle told Spectrum News, later adding: “I worry about the level of dysfunction and the message it sends to our country, and the rest of the world, when we're as dysfunctional as we are today. So we've got to see compromise both within the Democratic Party and between the two parties. And we're not seeing enough of that right now.”

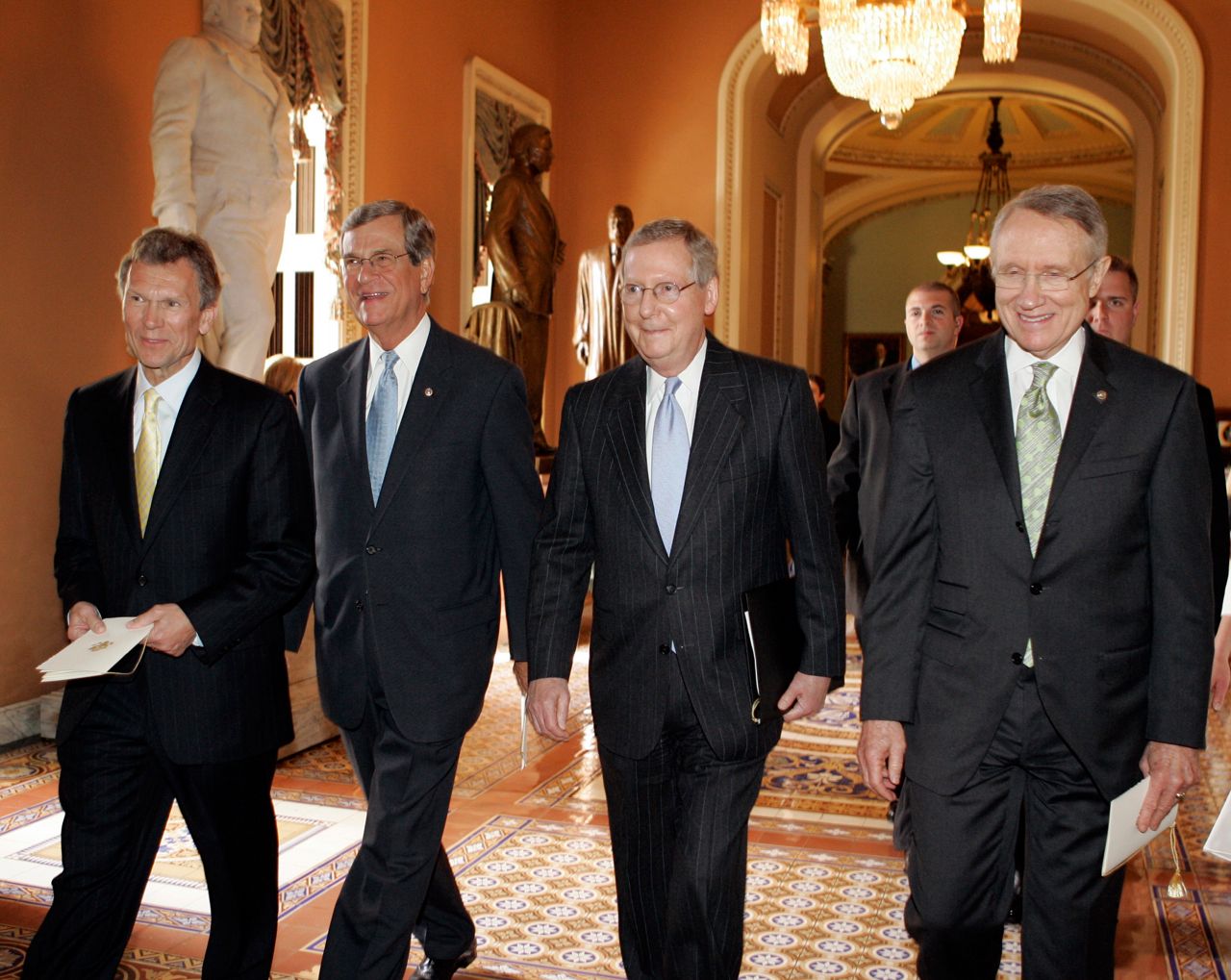

Daschle said he knows first-hand “how difficult it is sometimes to compromise,” as the last time the Senate was evenly split between Democrats and Republicans occurred during Daschle’s own tenure as Majority Leader — a position he handed off to Republican Trent Lott on Jan. 20, 2001, when the incoming George W. Bush administration gave Republican Vice President Dick Cheney the tie-breaking vote in the Senate.

The Republican’s narrow majority lasted only a few months, when then-senator from Vermont Jim Jeffords changed his party from Republican to Independent and began caucusing with the Democrats in June 2001, and Daschle again became Majority Leader.

Daschle and Lott formed a famously close relationship as they rotated leadership positions. Earlier this year, the two penned a joint Op-Ed for the Washington Post saying the process of negotiating committee rules for the 50-50 Senate was “one of the most difficult undertakings either of us faced in all the years we served in leadership.”

Still, Daschle recognizes that working across the aisle is more challenging now than ever before, saying: “Things have changed a lot in the time since I've left the Senate.” He blames the polarizing nature of politics on two factors: Social media and money.

“Truth is just an option today,” Daschle said. “And because truth is just an option, social media takes full advantage of that.”

“I really lament that in many ways I don't see politics as competitive as it used to be, in part because of money,” he added. “A typical senator today has to raise $20,000 each and every day he or she is in office. And if you don't have that kind of money to run for the Senate, there's no way you can be competitive.”

But there is, at the very least, one area where Daschle sees a potential for bipartisan agreement: Defending the nation from biological warfare.

It’s a deeply personal topic for the former lawmaker.

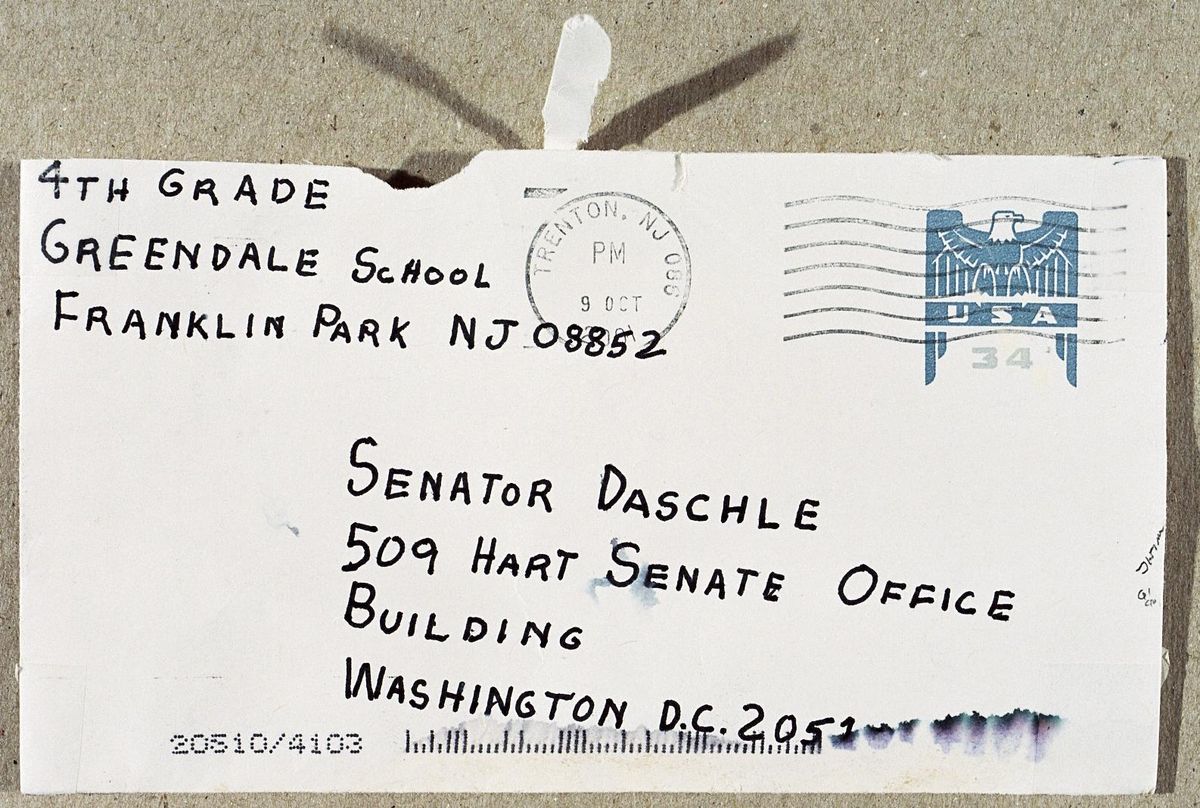

In October 2001, shortly after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks and when Daschle was serving as Senate Majority Leader, a man targeted Daschle and other public figures in a series of anthrax attacks. Daschle and nearly 30 members of his staff were exposed to the deadly toxin after opening mail sent to his office on Capitol Hill.

Other letters were addressed to NBC reporter Tom Brokaw, Sen. Patrick Leahy, (D-Vt.), and the New York Post. In total, five Americans died and 17 were sickened from the anthrax in what remains one of the worst series of confirmed biological attacks in the history of the United States.

“It was a transformational moment in my life,” Daschle told Spectrum News of the attacks. “It really created a tipping point that has caused me to dedicate a good deal of what I've been doing ever since to biodefense and to the need for us to be better prepared going forward.”

In the wake of the attacks, the U.S. government created BioWatch, an agency operating under the purview of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) tasked with detecting the presence of biological agents intentionally released into the air.

In the nearly two decades since it launched in 2003, BioWatch’s mission has been to provide “air-monitoring, analysis, notification procedures, and risk assessment” across 30-plus major metropolitan areas, which reportedly include New York, Los Angeles, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C.

But a recent report authored by Daschle and a coalition of former lawmakers and intelligence officials of both parties claims the BioWatch mission is “unclear and return on investment is minimal,” adding that the “technology was inadequate from the outset and has not improved over the past two decades.”

The report was issued by the Bipartisan Commission on Biodefense, a privately-funded group of both Democrats and Republicans founded in 2014 with the intent of reviewing the nation’s biodefense systems and offering suggestions to enhance them.

“Unfortunately, it's not proved out to be anywhere near what we had hoped it might be 18 years ago,” Daschle said of the BioWatch program. “It has many false alarms. It's very manual and you have to collect samples every day.”

The commission is calling for a “complete abolition or elimination of the BioWatch program,” Daschle said, with the hope that better research and deployment of new technologies will “create a far better ability to detect and respond when these crises occur.”

Those changes will require authorization from Congress and higher prioritization from the DHS, Daschle said. The Department of Homeland Security did not return Spectrum News’ request for comment.

Daschle remains hopeful that members of both parties will agree to take action on the issue.

“Biodefense basically is a bipartisan issue,” Daschle said. “There aren't Republican or Democratic advocates for biodefense. There are bipartisan supporters. What we lack are real champions or many of them.”

Bipartisanship, long a defining characteristic of Daschle’s political relationships, is a common thread in his advice for current lawmakers.

“It's important that we recognize that we may not get everything we want, but that's the whole concept of a democratic republic,” Daschle said. “It's reaching out and trying to recognize where that common ground lies and move this country forward.”

_crop)