The PowerPoint presentation was meant to connect with and, maybe just a little, impress the curious and bright-eyed who sat before them.

Pictured on the screen was a white-tail deer as teachers Leah Pautz and Bo Sahr explained to their Alaskan students that in Wisconsin, they would hunt these deer then drag them out of the woods.

The students looked at each other, then looked at the newbies in front of them with a collective stink eye.

“They were like, ‘Why can’t you just put it on your back and walk out,’’’ said Leah. “We were like, ‘What? You can’t do that.’’’

And a few months later, there she was, Leah Pautz, walking out of moose camp, a 125-pound moose leg strapped to her back, the marshy ground beneath her feet making her feel as if she was traversing a squishy mattress.

Welcome to Alaska.

****

Leah, from Neenah, and Bo, from Spooner, met as education majors while attending UW-Stevens Point.

They had just begun dating and were closing in on graduation when Bo mentioned he might like to do his student teaching in Alaska.

“Because, when will I ever get the chance to go up to Alaska?” Bo said.

Leah liked Bo and the idea, so she decided to go, too.

“It was only three months,’’ she said. “I’m like, I can handle something for three months. If I hate it, I can go back to Wisconsin and teach there.”

Today, some 4 1/2 years later, Bo and Leah are still there, living a life they never knew existed, falling in love with a people and culture that have occupied that land for over 2,000 years and, arguably, learning more than they have taught.

“I think for me, it has opened my eyes,’’ said Bo. “I had no idea about the Yup’ik culture before I came up here. I had no idea that there were places in the United States that had this type of lifestyle, subsistence.“I think for me, it has opened my eyes,’’ said Bo. “I had no idea about the Yup’ik culture before I came up here. I had no idea that there were places in the United States that had this type of lifestyle, subsistence.

“For me to experience that has really opened my eyes and has made me want to really learn more about this culture, along with other cultures in Alaska, that have been living here for thousands of years and living in these harsh environments. And so it has impacted me personally.”

Leah and Bo live in Nunapitchuk and teach at the Anna Tobeluk Memorial School, which has about 200 students, grades K-12. It is a village with just over 500 residents. Located on a tundra, there are no trees as far as the eye can see. Homes are on stilts, and not all have running water. The buildings in town are connected by a series of boardwalks. The Johnson River cuts through the middle of town, but there are no bridges. There are no roads to or within the village, which is only accessible by small aircraft, boats, and hovercraft as weather permits. In winter, snowmobiles are the main mode of transportation. There are no restaurants and just one general store. Internet is sparse, data capped and costs $300 per month. Teacher turnover is high.

So why, you might ask.

“If you’re willing to learn and humble yourself and say, ‘Yes’ to things, even though they might be scary, or uncomfortable, or inconvenient for you at the time,’’ said Leah, “I think the rewards are great.”

****

It was not long after they arrived when Bo and Leah were invited to a feast.

Now, in Nunapitchuk, when somebody hosts a feast, the entire town is invited. It may be 40 days after someone’s death to celebrate their life, or perhaps a birthday, or any number of reasons. And all the traditional foods are served.

“Soup is really big here,’’ said Leah. “Moose stew, moose soup, walrus, seal, bear.”

For dessert, there is what they refer to as Yup’ik ice cream; Crisco mixed with berries, water and sugar.

“It tastes like a smoothie,’’ said Leah.

There are traditions like feasts, and necessities like moose camp, fishing and logging.

Bo and Leah will travel about 60 miles up to the Yukon River Valley with another family and cut down trees, then load them on a toboggan-style sled and make the trek back to the village to use in their steam house.

“It’s called a maqii,’’ said Bo. “You have a stove in a man-made building and from there that’s how you bathe. You put wood into the stove and then pour water over the rocks on top of the stove, and it’s really like a hot sauna.”

Moose camp provides much of the food – what has become their favorite food – to survive. The first moose you “catch” traditionally is given away to elders and other residents in town who don’t have the ability to hunt.

“If you go and harvest a moose, you “caught” a moose,’’ said Bo. “I think it’s a way of honoring the animal.”

“Like, that animal presented itself to you, you were able to catch it, and it gives you life and can sustain you for the next few months,’’ said Leah.

Alaskan moose weigh anywhere from 800 to 1,600 pounds. And once you catch one, it’s nothing like hauling away a white-tail deer from Wisconsin.

“What they’ll do is quarter it up and then they’ll cut strips on the hide, so you can make like a backpack with the leg and then you can put the first straps over you and walk it out that way,’’ said Leah. “It’s the most ingenious thing I’ve ever seen.

“When we went hunting for the first time and caught a moose, it was like ‘What do we do? It’s like a cow on stilts.’ And they’re just like boom, boom, boom with one knife, cut it up and we’re able to haul it out.”

****

Through the single window in the classroom, light is just beginning to make its appearance for the day. It’s 10 a.m. At this time of year, by shortly after 4, it will disappear.

The school is the centerpiece of the community for much of the year. But there are many challenges far beyond the limited daylight.

Many students have to cross the Johnson River, a distance anywhere from 75 to 100 yards depending on where you are, and deep enough where the water comes up over your head in spots. In the late spring and early fall, they use boats to cross. In winter, it's snowmobiles. When it comes to early spring and winter.

“We’ve canceled school numerous times because the ice isn’t safe to travel across,’’ said Bo.

When it comes to teaching, Bo and Leah have learned that flexibility is first and foremost. Though both are trained in science, they’ve each had to teach a wide variety of subjects because of a wide variety of reasons.

“That’s the one thing being here, and living here and teaching here, is you have to be flexible,’’ Leah said. “You have to have a plan A, B and even C.”

And even in rural Alaska, COVID-19 has found them.

In early September there was an outbreak in the village. They went into complete lockdown for nearly a month, and many in the village who were positive used traditional medicines to get cured.

“We’ve had some buddies come that work in the village and work in the school and said, ‘If you’re feeling sick, just let us know, we’ve got some urine on hand,’’’ said Bo. “I’m like, 'I don’t know. I don’t know if I could do that.'”

Urine collected from a 2-year-old boy, then properly aged, combined with trips to the steam house was the preferred method of treatment for some families in the village.

“I don’t know if there’s any scientific evidence in that working or not,’’ said Bo, “But if you believe in that kind of thing and it’s working … ”

****

What brings the school together, literally and figuratively, is basketball.

“It’s the football of the Midwest,” said Leah.

If games are nearby, they will load the team in sleds behind snowmobiles and travel that way. If the games are a bit farther, they will use a vehicle and use the meandering Johnson River – which is turned into a road during the winter months – and travel that way. If it’s even farther, they will all hop into a bush plane, or Cessna 207, and hit the road.

“We’ll leave on Friday after school, fly to a village, you play that night against all the other teams that made it in – weather, or course, impacts that – and then once we’re done playing for the evening, each team gets an assigned room (within the school) and we’ll sleep there,’’ said Bo. “And then the next morning you play you remaining games.”

And sometimes, because of inclement weather, it will be two more days before they can fly home.

That time spent together, the relationships fostered in that environment, the connections that have been made have made thinking about the future hard, very hard.

“I know the day we do decide that our time is done here it will probably be one of the hardest days of my life, leaving,’’ said Bo. “That’s how much of an impact it’s had on me. It makes me sad thinking about that the day we leave, but just like anything else, you kind of know where your time is done and when you’re ready for your next journey in life.”

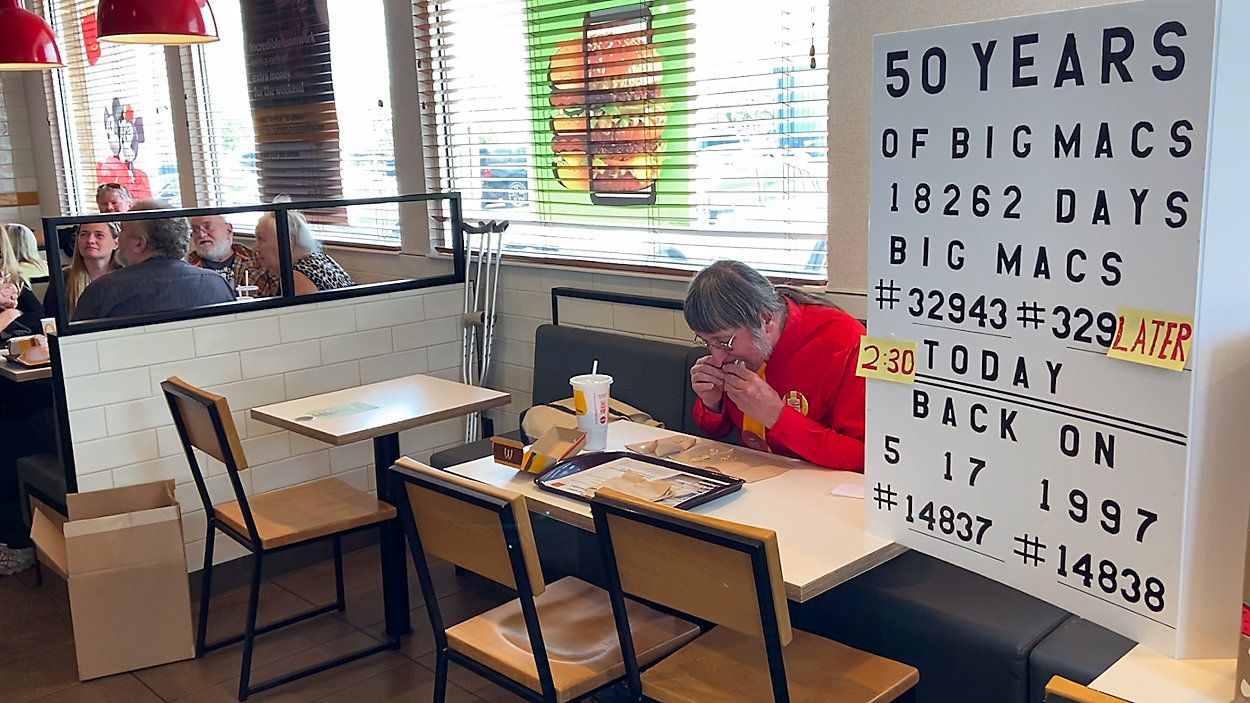

Bo and Leah will be married this summer. They miss their families, miss their friends, miss the many events they could not attend over the last few years and miss the idea of when you’re really craving a Big Mac, you can’t go get one.

“I think it’s kind of made me patient and flexible with things,’’ said Leah. “You make do with what you have. Everything here has to be brought in by somebody, and I think that kind of blows my mind sometimes. You have to carve out your own life here and you have to carve out anything you want, you have to go out and get it.

“Your world view, your world lens changes a little bit once you’re up here.”“Your world view, your world lens changes a little bit once you’re up here.”

At some point in the future, creature comforts will again be a part of their life. Family will be close. A slice of cheesecake will be available if they so choose.

But no matter where they go, who they teach or what they experience in Alaska, the way of life and the Yup’ik culture, will never leave their veins.

“I know they won’t forget us,’’ said Bo, “And I won’t forget them.”

If you have any story ideas for Mike Woods, contact him at Michael.T.Woods1@charter.com.

)