It’s just after 3 a.m. in mid-February.

It’s the end of the line – the E train in Queens. Car after car, New Yorkers have taken to the subway, some in desperate need of medical care or social services and housing.

In one car, six New Yorkers were sleeping. In the next car, there were three. Some had bags. Others had blankets. Many needed a place to go.

Above ground may be no different. Tyrone Braddy, a 70-year-old former city worker, sleeps downtown on Fulton Street most nights. His belongings are typically piled into one cart – a sleeping bag, blankets and more. He’s been homeless off and on for 15 years.

“We need help,” Braddy told NY1. “And you see more seniors out here, and it’s gotten worse. I’ve never seen this in my life.”

Braddy is diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder. When we spoke to him, he was not taking any medication.

“I am doing OK. I can think better,” Braddy said. “When I’m on psych meds, I can’t think. And I got to worry about people sticking me up and people walking up and saying, ‘Why you sleeping?’ and hitting me in the head with a pipe.”

The streets are dangerous, he said, recalling incidents where other people sleeping on the street have faced violence not too far away. Still, he does not want to go to a city homeless shelter.

“I lost my mother,” he said. “I lost my father. I lost my brother. I am the only one left.”

He is one of many New Yorkers who have languished on the streets or subways for years, in a crisis that only seems to be getting more severe.

NY1 has spent weeks interviewing experts, policy makers, and those sleeping on the streets and trains, scouring a system where people easily fall through the cracks, where men and women shuttle between the streets and area hospitals, failing to find stability in a clear mental-health crisis.

In some cases, it has dire consequences.

Twice this year, in two separate incidents, men who have experienced homelessness allegedly murdered two women.

One of them, Martial Simon, who is accused of pushing Michelle Go in front of a subway car in January, has a history of mental illness.

Shortly after these attacks, the new mayor said he would take on the problem, adding inter-agency outreach teams and cracking down on New Yorkers who violate MTA rules like lying down and sleeping, or smoking, and drug use.

“The train ends on the end of the line,” Mayor Eric Adams said last month. “Someone is on there with shopping carts, clothing bags, sleeping, unkempt. That’s not increasing anymore. It’s just not going to happen.”

The city started executing this plan late last month.

Even with these new efforts, this issue has been intractable for decades, and only worsening during the pandemic.

Dr. Tony Carino, the director of psychiatry at Janian Medical Care at the Center for Urban Community Services, told NY1 that during the pandemic, people on the street have had more of a challenge getting care in hospitals. Carino provides medical and mental health care to people living on the streets.

Coordination between providers in the community, like Carino, and hospitals has been challenging during COVID, as hospitals attempt to address surges in COVID-19 cases. There has been a real shift in continuity of psychiatric care for the homeless, he said.

“It’s been a challenge in many situations,” Carino said. “There are some situations where patients go in an emergency room, and they are evaluated quite rapidly, and some clinicians have reported they are not able to give clinical information, and the patient will be evaluated and discharged quickly without the clinician’s information from the community.”

Data from the state Office of Mental Health from the last quarter of 2020 show that at some hospitals, at least one quarter of psychiatric patients were returning to the emergency room within 30 days of discharge, continually cycling through the system. At Bellevue, 24% of patients came back to the E.R.

The mayor has blamed the crisis, in part, on the lack of inpatient psychiatric beds.

Beds at state-run facilities in the city have been declining for years. In 2006, the state’s psychiatric institutions in the five boroughs had nearly 2,100 beds, but that has steadily declined. Since then, the state has decreased its bed count by 35 percent. Now, there are only 1,351.

Officials said the state was moving away from institutionalization and moving towards providing care in the community, including adding thousands of units of supportive housing. According to the state Office of Mental Health, there is a specific process for when beds at its facilities can be taken offline. For instance, beds have to be vacant for 90 days. So, officials say shrinking these facilities was about “right-sizing” the state institutions.

At the same time, the trend was happening at hospitals and private facilities, too. In 2004, there were 3,338 beds at these facilities. In 2021, that number was 2,867.

And during the pandemic, it got even worse.

About 21% of the licensed psychiatric beds in hospitals and private facilities in the city were moved offline temporarily, according to the state Office of Mental Health, mostly to provide COVID-19 care.

Gov. Kathy Hochul has promised millions of dollars in state funding to bring those beds back, but there’s no timeline on when that might happen.

Those who have experienced homelessness explain it’s easy for someone to toggle back and forth between emergency rooms and the streets.

Daquion Goins sometimes goes to Pennsylvania Station to panhandle. He’s a regular face to passersby, who slide him dollar bills. He’s experienced homelessness for years. He now has a room in supportive housing, but he said his journey weaved through hospitals and psychiatric wards.

“I’ve probably been to the psych ward in one week, five times,” he told us, pausing from greeting commuters. “There’s seven days in a week and I’ve probably been five times.”

In some cases, experts and those experiencing homelessness said, people are discharged after getting stabilized, only to quickly cycle back after returning to the streets – repeating the process over and over.

“Some people love to go from homeless to the psych ward because they know they can have a meal, they have a bed to sleep in for a week or two, they have a therapist they can talk to,” Goins said.

Last month, state officials released new guidance to mental health providers and hospitals, potentially expanding their ability to hold people involuntarily. The guidance said doctors need not only use an “overt risk of violence” to keep someone involuntarily for hospitalization or evaluation. The guidance now says someone could also be held if they display “an inability to meet basic living needs.”

It was a directive aimed squarely at people experiencing homelessness in mental health crisis.

“The case law does support keeping people in the hospital who are of danger to themselves or others and that does not just mean I am going to kill myself,” said the head of the city’s public hospital system, Dr. Mitchell Katz. “It could mean, ‘I can’t feed, clothe, myself, I don’t have a plan.’ So, that period of time of healing is longer.”

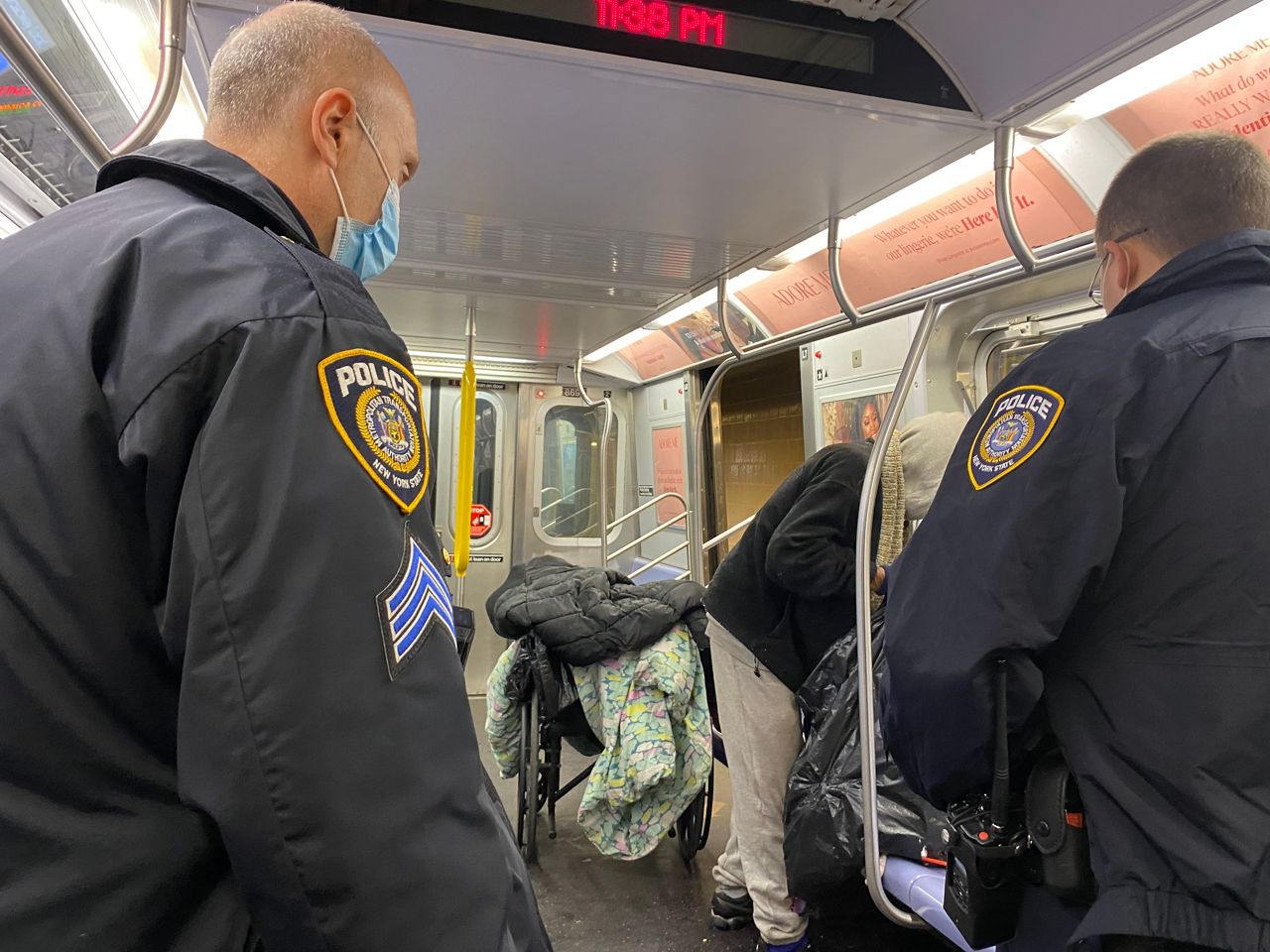

On top of that, the mayor is adding as many as 30 new interagency teams of outreach workers, medical personnel and NYPD, in part to potentially step up involuntary removals.

It’s a practice that can be jarring when seen up close.

It was already on the rise last year. The number of times Department of Homeless Services outreach workers involuntarily removed someone from the street or subway to a hospital for evaluation spiked dramatically in 2021 compared to the year before, climbing 431%.

Sources in the Department of Homeless Services say they have added outreach workers and nurses to its ranks, but they also acknowledge during the pandemic cases have become more challenging.

Of course, there are solutions besides hospitalization.

Kenneth Henry lived on the streets for about three years. He now has a stable roof over his head at a supportive housing facility in Times Square.

He is diagnosed with bipolar disorder and gets his services on site. There is medical care, psychiatric care and other services for the formerly homeless.

“They need help,” Henry said. “Some people need a lot of help. Some people need a little help. That’s one of the best things about this particular building, is it has all of these services.”

The facility is run by Breaking Ground, which also does outreach services to those living on the streets. Its head, Brenda Rosen, told us her team has seen a 1,000% spike in caseloads in the Midtown area.

Having more facilities like this could help address the increase, she said. Advocates said the city needs thousands more units of supportive housing.

“It’s no doubt a mental health crisis,” Rosen said. “There are people who are unsheltered right now that need significant help. Housing is health care. You cannot ignore the fact that housing with on-site supports has been proven time and time again to be a long-term solution for those that have substance abuse disorder for those that have mental illness, for those that have both."

Officials at the city and state level have promised more shelter beds and supportive housing. Another 500 shelter beds should be online in six months, according to a spokesperson for City Hall, and another 500 units of supportive housing should be up by the end of the year, according to the governor’s office.

It’s unclear if it will be enough if hundreds of people are suddenly removed from the subways or streets.

As for Braddy, his case worker said he should soon be getting into supportive housing for people with mental health issues - one of many people who hope to get one step closer to stability.