The rate of a rare blood clot disorder in the brain was much higher in people infected by COVID-19 than in those who had been given vaccines for the virus, a study conducted by researchers at the University of Oxford found.

What You Need To Know

- A study conducted by researchers at the University of Oxford found that the rate of a a rare blood clot disorder in the brain was much higher in people infected by COVID-19 than in those who had been given vaccines

- The scientists say cerebral venous thrombosis occurred at a rate of 39 in a million patients with COVID-19, compared to about five in a million for those given the AstraZeneca vaccine and four in a million for those given the Pfizer or Moderna shots

- The researchers also analyzed the rates of portal vein thrombosis, a clotting disorder of the liver, and also found that risk was much higher among those infected with COVID-19

- Pfizer said it has found no evidence that its vaccines cause blood clots; the CDC director also said health officials are not seeing the same type of reactions in people given the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines as they are seeing in those administered the Johnson & Johnson shot

The scientists say cerebral venous thrombosis, or CVT, occurred at a rate of 39 in a million patients within two weeks of being diagnosed with COVID-19. That is about eight times higher than the blood clots found in people given the AstraZeneca vaccine (about five in a million) and 10 times higher than those given the vaccines developed by Pfizer and Moderna (four in a million).

“We’ve reached two important conclusions,” Paul Harrison, professor of psychiatry and head of the Translational Neurobiology Group at Oxford, said in a news release. “Firstly, COVID-19 markedly increases the risk of CVT, adding to the list of blood clotting problems this infection causes. Secondly, the COVID-19 risk is higher than [seen] with the current vaccines, even for those under 30; something that should be taken into account when considering the balances between risks and benefits for vaccination.”

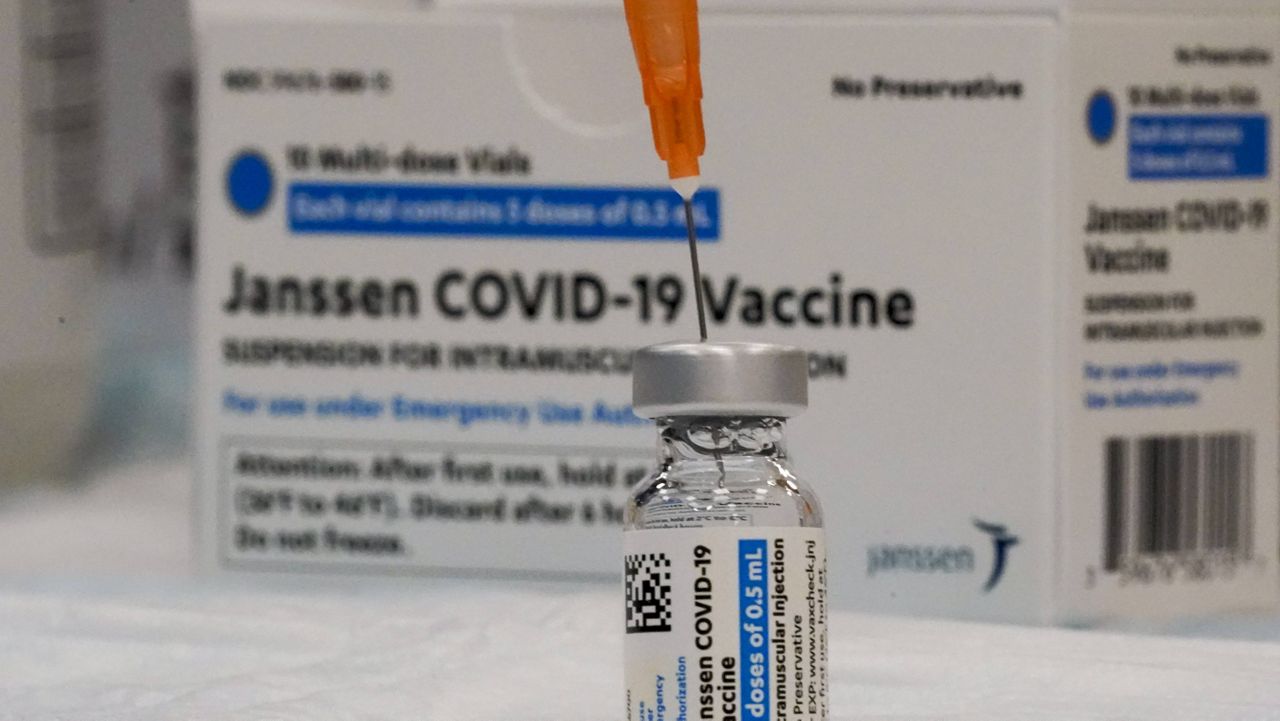

The study did not examine the Johnson & Johnson vaccine. The U.S. paused the administration of that vaccine this week amid concerns over brain and abdominal blood clots in a handful of recipients.

Several countries last month similarly paused inoculations using AstraZeneca’s vaccine, which was developed in partnership with Oxford, after at least 37 people who were vaccinated experienced blood clots, with at least four dying. The countries resumed vaccinations after the European Medicines Agency, the E.U.'s medical regulator, declared the vaccine to be “safe and effective,” but it added that it "cannot rule out definitely a link" between blood clots and the shots.

The AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson vaccines both use antivirus vectors, while the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines use messenger-RNA technology.

The Oxford researchers used data from an electronic health records network to analyze more than 513,000 patients who had tested positive for COVID-19 and about 490,000 who had received the Pfizer or Moderna vaccines. They compared that to the general population as well as estimates from the European Medicines Agency for the AstraZeneca vaccine. The rate of CVT in the general population was 0.41 in a million.

A pre-print of the study was published on the Center for Open Science’s website and has not been peer reviewed. The researchers noted that one area that requires further research is whether COVID-19 and vaccines lead to CVT by the same or different mechanisms.

The researchers also analyzed the rates of portal vein thrombosis, a clotting disorder of the liver, and also found that risk was much higher among those infected with COVID-19. There were 436.4 cases in a million among those who had the virus, 44.9 in a million among those given the Pfizer or Moderna vaccines and 1.6 per million among those given the AstraZeneca vaccine.

“The signals that COVID-19 is linked to CVT, as well as portal vein thrombosis ... are clear, and one we should take note of,” said Dr. Maxime Taquet of Translational Neurobiology Group, one of the study’s authors.

While potential links between the Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca vaccines and blood clots have received much attention globally in recent weeks, some might find it surprising that the study found that those receiving the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines developed CVT at similar rates.

Pfizer said in a statement to Spectrum News that it has “conducted a comprehensive assessment of ongoing aggregate safety data” for its vaccine and found “no evidence to conclude that arterial or venous thromboembolic events, with or without thrombocytopenia, are a risk associated with” the shots.

Dr. Rochelle Walensky, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, also said Wednesday that U.S. health officials are not seeing the same type of reactions — blood clots in combination with low platelet counts — in people given the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines as they are seeing in those administered the Johnson & Johnson shot.

Health officials have not yet determined whether there is a link between the Johnson & Johnson vaccines.

Moderna did not respond to a request for comment.

Ryan Chatelain - Digital Media Producer

Ryan Chatelain is a national news digital content producer for Spectrum News and is based in New York City. He has previously covered both news and sports for WFAN Sports Radio, CBS New York, Newsday, amNewYork and The Courier in his home state of Louisiana.