Advances in technology and genetic research have paved the way for one of the most ambitious research projects to date, which hopes to find needed answers to common and rare diseases with a more diverse population of participants. Health reporter Erin Billups takes a look at the All of Us program, which Congress has dedicated $1.4 billion to.

Ever-expanding waistlines in the United States has led to a sharp increase in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, affecting 34 percent of the population. A subset of these patients have NASH, the most severe form of the disease.

Matthew Park has this excessive accumulation of fat in his liver, but he doesn't fit the profile.

"If I look at even in the waiting room, there's like, patients for the liver transplant center here at Columbia, and I don't feel like those people look like me," said Park. "What I mean by that is, they're bigger, larger. For whatever reason, I have I think an anomaly."

Park is an anomaly. His doctor, Julia Wattacheril, a transplant hepatologist at NY Presbyterian/Columbia, said, "It would be immensely valuable to be able to determine who has NASH and who doesn't. Earlier, better, with a simple blood test."

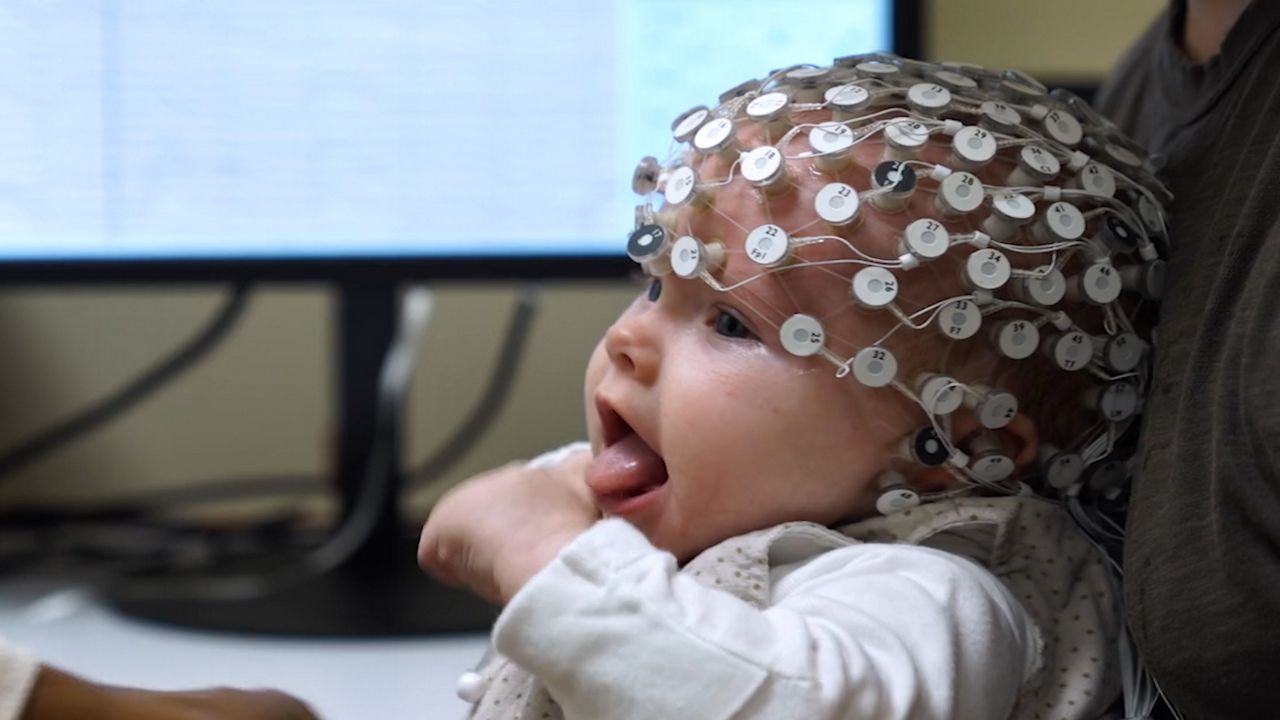

There are so many diseases shrouded in mystery. Available data on many conditions, like NASH, are limited by the pool of people involved in research. Which is why the National Institutes of Health has launched All of Us, an ambitious long-term study to better understand human diseases.

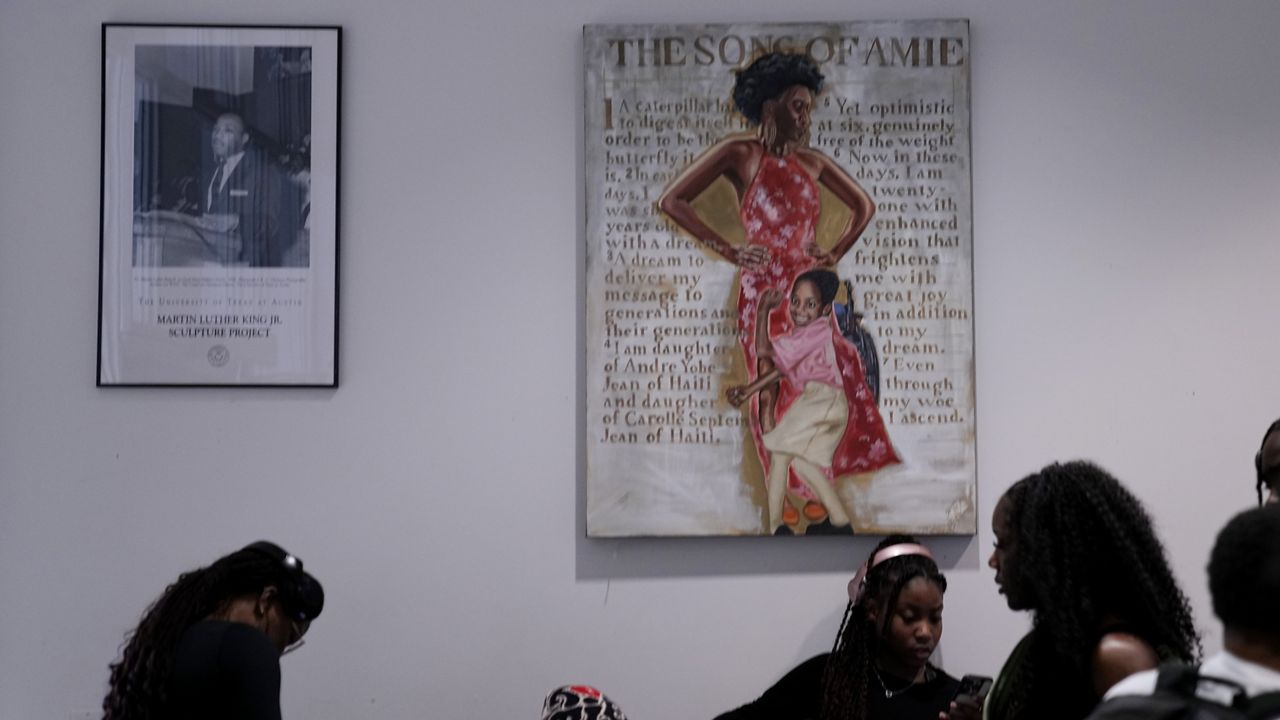

"We're sort of changing the paradigm here of having, you know, very heavily European ancestry data represented in the data set to moving to a very diverse set of data," said Stephanie Devaney, deputy director with the All of Us Research Program. "So when researchers are asking questions about who stays healthy and why, they're working from a data set that is more reflective of the population."

Open enrollment for All of Us began in May at 120 sites across the country. So far, more than 86,000 Americans are enrolling. It's expected to take four to five years to reach 1 million participants.

Wattercheril is helping to enlist patients at NewYork Presbyterian Columbia.

"I think there's a strong hope that health care, in the grandest sense, will be a little bit more fair, that when we issue recommendations, that person will feel like those recommendations apply to them specifically," Wattacheril said.

Park has signed on, his measurements taken, blood drawn with the hope the future will understand his disease a little better.

"I think I just put it out there to trust that this is going to help in the long term," Park said.

Researchers will start to have access to the collected data as soon as early next year.

For more information, visit https://www.joinallofus.org/en.