Most people spend their waking and sleeping hours inside a building, but rarely do we think about whether that building promotes good health or is making people sick. This disconnect may be most stark when looking at the nation’s school building infrastructure. In her latest Exploring Your Health episode, National Health Reporter Erin Billups takes a closer look at how the school building itself is affecting the health of students and staff.

What You Need To Know

- Underinvestment has created a crisis that's affecting the health of U.S. school buildings

- Many public schools suffer from poor air quality, lead in drinking water, and many more health issues

- Studies have show that improving the health of classrooms can improve test scores

The to-do list of facilities projects at Charlotte Mecklenburg Schools in North Carolina continues to grow. Dennis LaCaria, Executive Director of Facilities Management, said many of the buildings no longer fit the needs of the district.

“We've got stuff that dates back to literally the early 1900s,” said LaCaria. “You have buildings, therefore, that were built before central heating, air conditioning.”

“One of the biggest things we struggle with is the HVAC, being able to control that. On days when you'd think the air would be on and it all of a sudden, it's 90 degrees and no air,” said Principal Rick Parker of East Mecklenburg H.S., part of CMS.

Maintaining schools’ facilities is an unavoidable race against time and nature that every school district deals with. Like CMS, districts often resort to the use of portable classrooms as current facilities fail to meet growing needs. It's a short-term fix turned long-term solution for classroom space.

“Portable classrooms are notoriously the worst when it comes to things like air quality,” said Rachel Hodgdon, President and CEO of the International Well Building Institute.

Hodgdon has been working to draw attention to what she calls a national crisis– the health of the buildings students and staff spend most of their time in.

“Buildings are a prescription for public health. Schools are a particular kind of patient,” said Hodgdon to attendees of the 2023 Well Building Conference in Washington D.C.

Four former U.S. Surgeon generals pointed to the role the pandemic played in getting a critical mass of leaders to pay more attention to the quality of school buildings.

“This was well brought to the forefront, emergently, during COVID when we found out that the filtration systems didn't work,” said Dr. Richard Carmona, 17th U.S. Surgeon General.

“Schools have to be taken more seriously if you want your kids to learn,” said Dr. Antonia Coello Novello, 14th U.S. Surgeon General.

“Many many of our schools suffer from poor, really unacceptable air quality. And that has a whole host of implications,” said Hodgdon. “Imagine how much more continuity of education we would have if teachers and students weren't chronically suffering from cold, from the flu, from RSV, and from Covid-19.”

The price tag to modernize though, is hefty. For CMS and other districts, public funds don’t come close to covering the cost of fully modernizing schools.

“The federal government doesn't really provide any funding at all for capital needs for schools. And the state of North Carolina, for example, has not issued a bond to their schools since the late 1990s,” said LaCaria.

“We are underinvesting in our schools to the rate of $85 billion a year. That's up 85% from five years ago,” said Hodgdon. “Every year that we delay on bringing our schools into a state of good repair, that tab is going to get larger.”

Among the school districts able to modernize, many rely on the bond referendum, a taxpayers vote to determine whether the local government will foot the bill of school capital plans.

“Successful school bond initiatives are one of the only tools in our toolkit for improving, retrofitting, [and] rebuilding our schools,” Said Hodgdon. “It's just not happening consistently enough across the country, and many districts simply can't afford to tax themselves more to undertake these repairs.”

Hodgdon says oftentimes these initiatives fail because many don’t see the link between crumbling infrastructure and the health of the people who use the buildings regularly.

Health connections to issues like failing to replace lead-lined water pipes. “The majority of school districts aren't doing comprehensive, regular water quality testing, largely because they know if they find a problem, they can't afford to fix it,” said Hodgdon. “Lead will bioaccumulate in a child's system. It means that these kids will be plagued by learning issues and by health issues in many instances, potentially for the rest of their lives.”

In November 2023, residents of the CMS district voted to approve its $2.5 Billion bond referendum which will fund 30 out of its 125 facilities improvement projects.

“We're fortunate to be in a community that's in a position to support its schools and that makes the choice to support its schools. But not everybody has the same sort of advantages that Charlotte-Mecklenburg schools has,” said LaCaria.

CMS officials are also keeping track of the difference new school buildings are making, so they can better understand why they are seeing improvements in academic performance.

“We've seen decreased absenteeism. So, more students showing up, a sign of less illness,” said LaCaria. “We're seeing, you know, fewer staff illnesses. More contact hours has been one thing. We've seen improvements in the standardized testing at those schools as well.”

In the age of school shootings, CMS is designing campuses with safety and mental health in mind. East Meck High School will go from nine buildings to three. A previous bond initiative led to the consolidation of West Charlotte High School from 16 buildings to one.

“Having those single points of entry, creating an environment where the students know that they're safer inside the building, creating fewer opportunities for kids to just wander on and off campus or in between buildings, or even not our students,” said LaCaria.

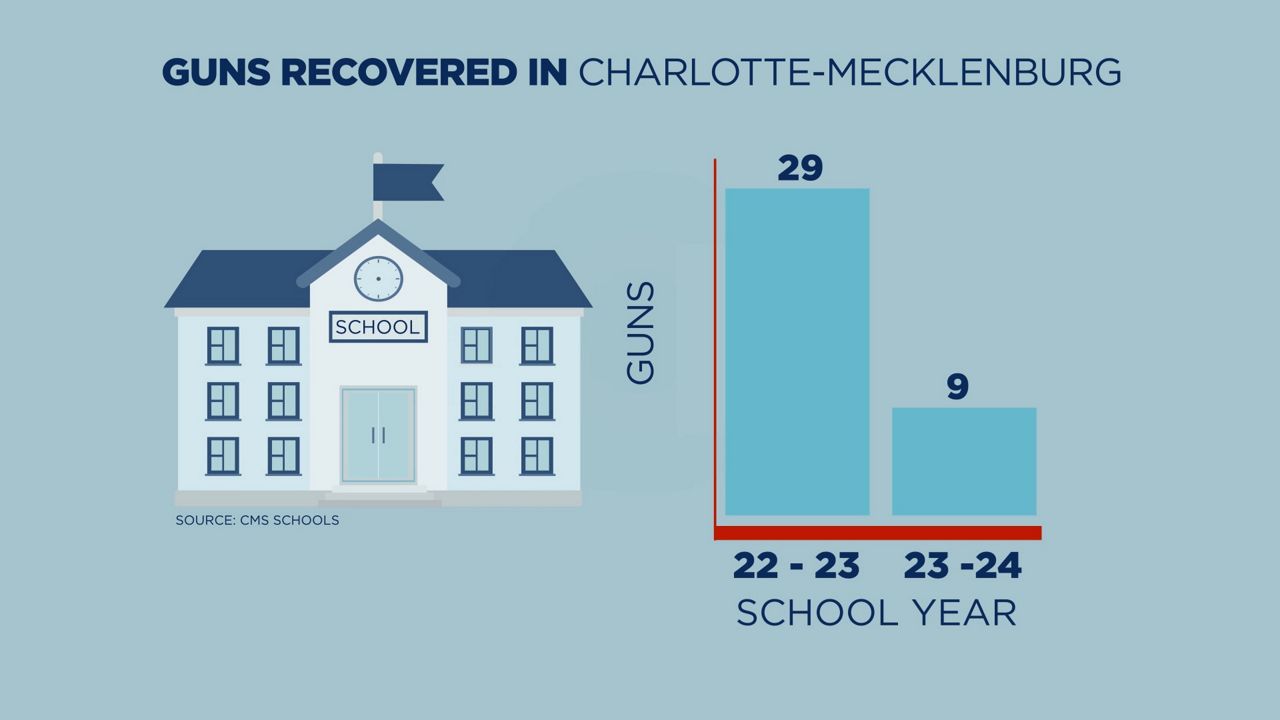

As a result, CMS has seen a significant decrease in guns in its 184 schools. “All of that improves the general feeling of safety on the campus,” said LaCaria.

When students feel safe, they're able to learn better. But Hodgdon said the burden to overhaul and modernize schools should be shared beyond individual districts.

“We have to tell the federal government that paying less than 1% of annual school facilities, maintenance, improvement and rebuilding is pathetic.”

More on that in part two of our series on sick schools.