One in 36 children are diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder. But of those, very few actually know what specific gene mutation may be behind their diagnosis. National Health Reporter Erin Billups takes a look at how early genetic testing can improve treatment options and quality of life for patients.

“He's happy. He's outgoing. He's more outgoing with adults than he is with children. He loves water play. Loves to swim,” said Genie Egerton-Warbuton, who can’t help but smile herself when she speaks about her 11-year-old son Rowland.

Like many expecting parents, during her pregnancy with Rowland, Egerton-Warbuton underwent prenatal testing.

“I had to have a cesarean section. I'll never forget the doctor saying, you've given birth to a perfect, beautiful baby. Healthy, you know, healthy little boy that we know doesn't have any sort of issues or genetic abnormalities, etc. from this test,” said Egerton-Warbuton.

But from his notched eyelids at birth to missed developmental milestones, Egerton-Warbuton, a former preschool teacher, knew something wasn’t right.

“It's not normal for a child not to walk until they're two. And even his gait wasn't appropriate. And he was able to say some words, but then he was losing the words. He was able to pick up food and kind of feed himself. But then the next day, he needed to be spoon fed. It was just kind of, things did not feel right,” said Egerton-Warbuton.

When Rowland was four, he underwent another round of genetic testing and was finally diagnosed with a form of autism called ADNP syndrome — a deficiency of the activity-dependent neuroprotective protein — a mutation that wasn’t included in the test when Rowland was in utero.

“We know that protein is supposed to play a really important role in brain development,” said Dr. Alex Kolevzon, director of the Seaver Autism Center at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City, of the ADNP deficiency. “The hallmarks of ADNP syndrome, like autism, are social communication problems.”

Kolevzon said ADNP is now included on the genetic screening test for autism, along with more than 200 other known gene mutations that cause varying degrees of autism. ADNP accounts for about 0.2% of autism cases, but there may be even more who have it. Kolevzon says it is time for more families to get their kids tested.

“Oftentimes, families don't fully appreciate the value of genetic testing. You know, they have a child, the child that has autism. And it's not clear how knowing what the genetic causes will actually impact the child's life,” said Kolevzon.

The sooner families and doctors know, the better, said Kolevzon. While not every case of autism will have a genetic abnormality, it’s estimated that about 10 to 30 percent will find a known cause through testing.

“For us, there's a kind of a shift towards more personalized medicine. And so, you know, if you know exactly what's wrong with the biology, it gives you an opportunity to develop more targeted treatments,” said Kolevzon.

Rowland was enrolled in a study led by Kolevzon, with nine other kids with ADNP Syndrome.

Each child was given a very low dose of ketamine. Kolevzon said the drug may promote synaptic plasticity or nerve cell growth. That’s what they eventually found, participants saw improvement in sensory sensibilities, hyperactivity and repetitive behaviors. Larger studies are needed to confirm the findings.

“After the infusion, the next day he said, ‘Mommy,’ which was, you know, amazing,” said Egerton-Warbuton. “And we noticed that he was able to navigate a city street without walking into people.”

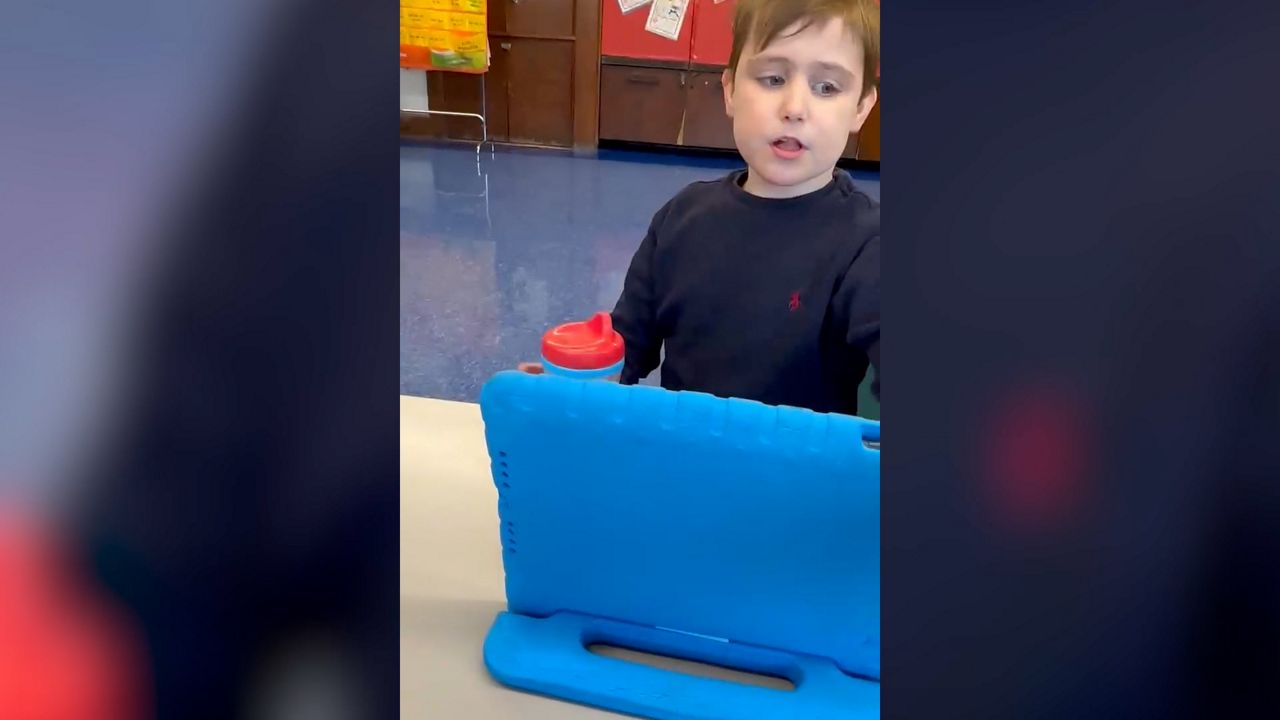

Rowland continues to work on further developing his speech. He is also learning to use a device that will help him communicate.

Egerton-Warbuton said her hope is that as more people with autism and other brain-based disorders are tested, more resources will go toward finding transformative genetic therapies for ADNP and other disorders.

“So many of these hospitals do want to collaborate and do want to help these children. But it's very hard when you have a small amount of children and adults,” said Egerton-Warbuton. “You just feel kind of stuck.”