Increased access to marijuana has led to a growing problem. Now several experts and health providers are trying to get the word out to caregivers — keep your edibles out of the reach of children. National Health Reporter Erin Billups has more on the alarming trend.

As more and more states legalize the recreational use of marijuana, an underappreciated consequence has emerged — a rapid rise in very young children needing emergency medical care after eating cannabis treats.

”There's more and more presentations to the E.R. every single day. And quite frankly, it's very scary because the presentations are so variable,” said Dr. Elise Perlman, Pediatric Emergency Medicine Physician at Northwell Health in New York.

Perlman and emergency medicine toxicologist Mark Su penned an article in the JAMA Pediatrics Journal, last fall — ringing the alarm.

“This is a public health problem that I think really needs to be addressed and people need to understand it,” said Dr. Mark Su, who also serves as the director of the New York City Poison Control Center.

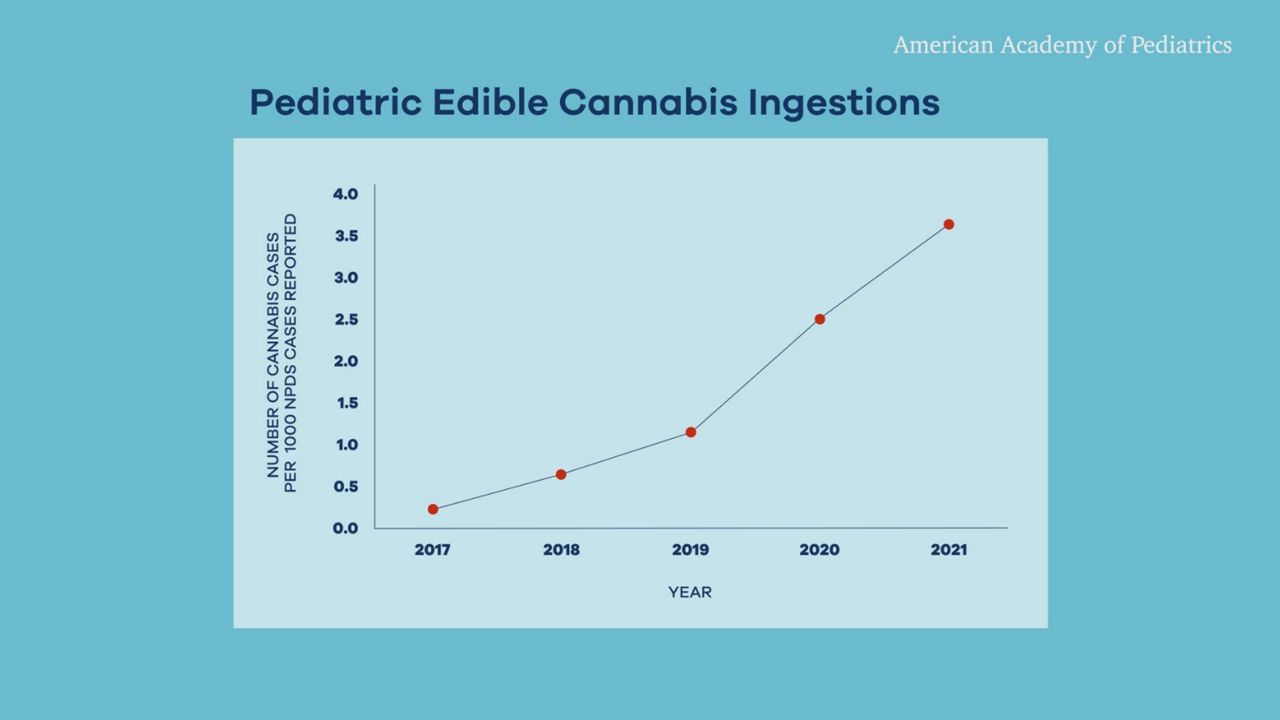

The American Academy of Pediatrics published a study this January showing a 1,375% increase in edible cannabis exposure among children younger than six between 2017 and 2021.

The largest increase in pediatric cannabis ingestion was between 2019 and 2020. Researchers say COVID-related quarantine may have offered children more opportunities to explore and find edibles at home. Oftentimes, caregivers don’t know the child has eaten THC-laced sweets.

Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the major psychoactive component of cannabis plants; the drug is known to cause depression of the central nervous system. Children present to emergency rooms with a wide range of symptoms, the most severe being seizures and breathing problems. Some patients even require intensive care.

More often, though, Perlman says children may simply seem overly tired. “They might not want to wake up. They might not be eating or drinking and just want to sleep,” said Perlman. “They may be slurring their words. When you see this, you should certainly present to the E.R. for evaluation.”

The Pediatrics study found 90% of cannabis ingestion occurred within the child’s home. The highest number of accidental ingestions were among two and three-year-olds. Toddlers are more likely to explore, test boundaries and climb to reach items.

Su and Perlman urge caregivers to push shame, guilt, fear or stigma aside and let hospital staff know if the child could have eaten edibles. It may help prevent unnecessary invasive tests required to rule out more serious conditions.

“These ingestions often mimic other acute illnesses like sepsis, bacteremia, meningitis, and those have life changing consequences if you don't pick them up,” said Perlman. “It's our job to figure out what's going on.”

When cannabis is the known culprit, the care is typically supportive monitoring. “We just keep patients safe and comfortable and we treat them symptomatically. If they have vomiting, you give them something to stop the vomiting. If they're dehydrated, you give them some I.V. fluids,” said Su.

Another major issue is the lack of regulation for how manufacturers package cannabis products. While some states require clear warning labels, most don’t. It is a big issue, as many edibles are sold in brightly colored packaging mimicking popular sweet treats.

Further complicating matters, there is no standard dosing for THC used in edibles, said Su.

“The dosage is not particularly regulated, so an THC gummy could have anywhere between ten milligrams of THC to maybe 100 milligrams,” said Su. “So it is very easy, if you're cannabis naive, to take a cannabis gummy with a large amount of THC. You could clearly get very sick from it.”

Both emergency care doctors are urging primary care providers to help get the word out. “I think organizations like the American Association of Pediatrics should be coming out with statements, educating the providers to be aware,” said Su. “Providers should be screening for this during office visits and educating parents and caregivers of the dangers.”

Authors of the study published in Pediatrics offer some simple steps caregivers can take to keep weed treats out of reach including storing edibles in a container with child-proof locks, in a location outside of the kitchen away from other food items. Experts suggest that adults should not use or eat cannabis in front of children, so they’re not tempted to mimic.

“The most important thing is not to feel ashamed or embarrassed and to seek medical attention if needed,” Perlman. “We're obviously here to help and we want to help and make sure that our kids stay safe.”

It’s not just children at risk. Veterinarians, too, are seeing a rise in animal cannabis overdoses and are advising owners to keep edibles out of reach of their pets.

Call poison control if a child has ingested or an adult has overdosed on cannabis — the number is 1-800-222-1222.