This story is the third installment of our three-part series on the country’s diabetes epidemic.

BRONX, NY - Chris Norwood knows what the country’s diabetes crisis looks like. She sees the effects of widespread disease every day on her way to work. The neighborhood around her South Bronx office is the epitome of a community plagued by diabetes — people in wheelchairs with missing feet, a dialysis center every few blocks. “Something's terribly wrong, that this is allowed to happen,” says Norwood, “that you can see this throughout the community.”

Inside her office, however, Norwood and her team are rewriting the narrative.

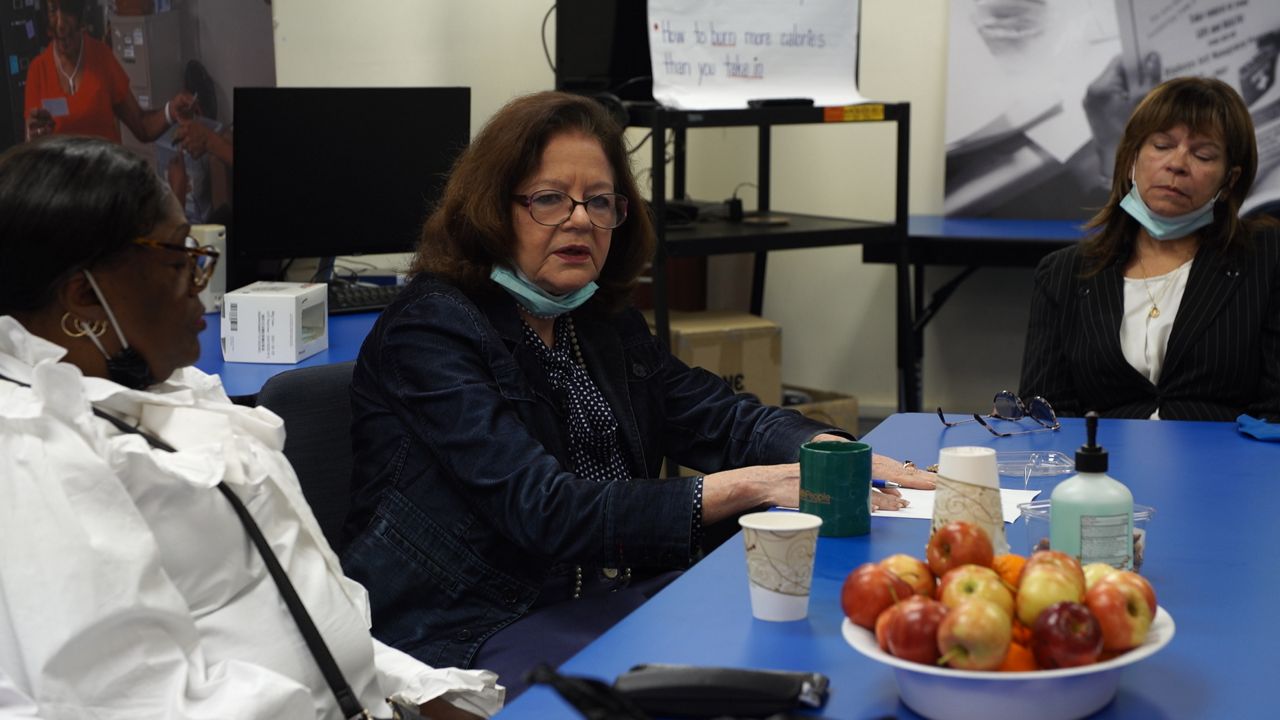

On a brisk March morning, a group of New Yorkers gathered in a windowless meeting room on the second floor of an unsuspecting storefront. Stacks of boxes and filing cabinets occupied much of the space. The walls were decorated with team photos and various posters listing nutrition facts and other health information related to diabetes. A banner along the far wall identified this as the office of Health People. At the center of a long folding table, various snacks were laid out for the attendees — apples, oranges, mixed nuts.

This is a meeting of diabetes peer educators — most of them diabetics themselves — dedicated to teaching their fellow Bronx residents how to better control their disease. They follow the Diabetes Self-Management Program, a federally recognized six-week curriculum designed to give people the knowledge and tools they need to better manage the condition. It covers basics like nutrition, reading food labels, and A1C monitoring.

Many of the peer educators, who are alumni of the program, call it life-changing. Loretta Fleming lost over 100 pounds. Elton Santana says he lowered his A1C so much that his doctor took him off medication. Norwood reminds them that it’s about even more than that.

“I know that your work has outright saved many people’s lives,” she tells them. “It’s unquestionable.”

Norwood attributes the program’s success to lessons she has learned over a 30-year career which started with a battle against a different health crisis — the combined epidemics of drug use and AIDS that inundated the South Bronx in the 80s and 90s.

“Everyone was so confused. You know, they didn't know anything. They thought maybe this was familial or something,” Norwood remembers. “Everybody was getting it.”

But in the midst of that crisis, Norwood witnessed a motivation to help within the most vulnerable communities. “At that time, women who had been diagnosed with AIDS had on average a year to live. And when we put out word and said, Do you want to be a peer educator? You want to go out in the community? Many women said they did. They said they wanted to spend whatever time they had left helping other people.”

From that experience was born the Health People model for peer education. Over the years, the organization evolved to meet the needs of the community, launching additional peer-led initiatives aimed at other prevalent health issues, like asthma and smoking addiction.

Then, Norwood says, diabetes rates exploded. “It became the most overwhelming thing. And at the same time, it's still the most unaddressed.”

She knew that this epidemic, like the others she had battled, would need to be fought at the grassroots level, by those who knew the lay of the land. “Peers are from your community,” says Norwood. “If they're doing diabetes, they'll have diabetes or prediabetes, but they'll also live in public housing in your community and you can feel comfortable with them.”

Peer-led programs are also faster to get up and running than other types of programs that might require doctors, nurses or clinical facilities. Health People’s training for peer educators is only four weeks long, meaning participants can be out, working in the community, in just a month.

Today, given the growing scale of the diabetes crisis, Norwood says more hands on deck is what’s needed to fight it.

“We have to massively train local groups,” she says, “and I mean massive, like an army.”

But building an army requires funds, and Norwood says the money to expand the program has been hard to come by. She believes that for other organizations, the lack of funding is a barrier to launching similar programs.

“The city has a $1.6 billion public health budget that's more than most countries. And the state, I can't even count how many billions they have now with the federal aid,” says Norwood. “Neither one of them has a diabetes plan.”

Despite the success of Health People’s program, Norwood spends much of her time figuring out how to keep the lights on. They piece together most of their operating budget from foundation grants, or from one-time government funds earmarked for other purposes, such as reducing emergency room visits.

Norwood insists it’s a costly oversight — programs like hers have been proven to save not only lives, but also tax dollars.

“The average cost for dialysis now is $90,000 a year, per person.” says Norwood.

A recent study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons calculated the average cost of a lower limb amputation at more than $50,000.

The Diabetes Self-Management Program costs less than $1,000 per patient.

“It is a missed opportunity and a bad financial decision to not provide the peer educational support,” says Congressman Raul Ruiz.

Ruiz, who serves as Vice Chair of the Diabetes Caucus, has fought the diabetes crisis on multiple fronts — first as an emergency room physician, and now as a lawmaker representing Southern California.

“The prevention, and the management, and the peer education community health worker model is an incredible cost savings,” he says.

This is especially true for Medicare and Medicaid programs, which cover more than half the cost of diabetes care in the U.S.

Podcast

Erin Billups joined Spectrum News NY1's Errol Louis' podcast "You Decide with Errol Louis" to discuss their new collaborative special report “USA1C: Fighting the Rise of Diabetes,” which is currently airing on Spectrum News nationally.

Tackling the crisis has been a focus for Ruiz. One piece of legislation he’s been working on would allow Medicare to cover self-management training in community-based settings and eliminate the copay for Medicare patients.

If it passes, it would be a substantial step toward making programs like this more widely available. Ultimately, though, Norwood believes bigger changes are needed to reshape the current system, where there’s often more incentive to treat issues than to prevent them.

“People have been turned into commodities for a sickness industry and we have to look at that squarely,” says Norwood.

Large-scale change, Ruiz says, will require the government to readjust how it looks at our healthcare system.

“The way that the economists in the Congressional Budget Office and others take into consideration scoring of the cost of pieces of legislation, they do not take into account future cost savings,” he explains. “They only factor in the immediate costs and their projections over the next five, maybe ten years, but they do not put into the cost savings for the prevention of an amputation into those equations.”

It’s a policy change that Ruiz says he’s fighting for. But altering the way large institutions view and treat chronic disease is no small feat.

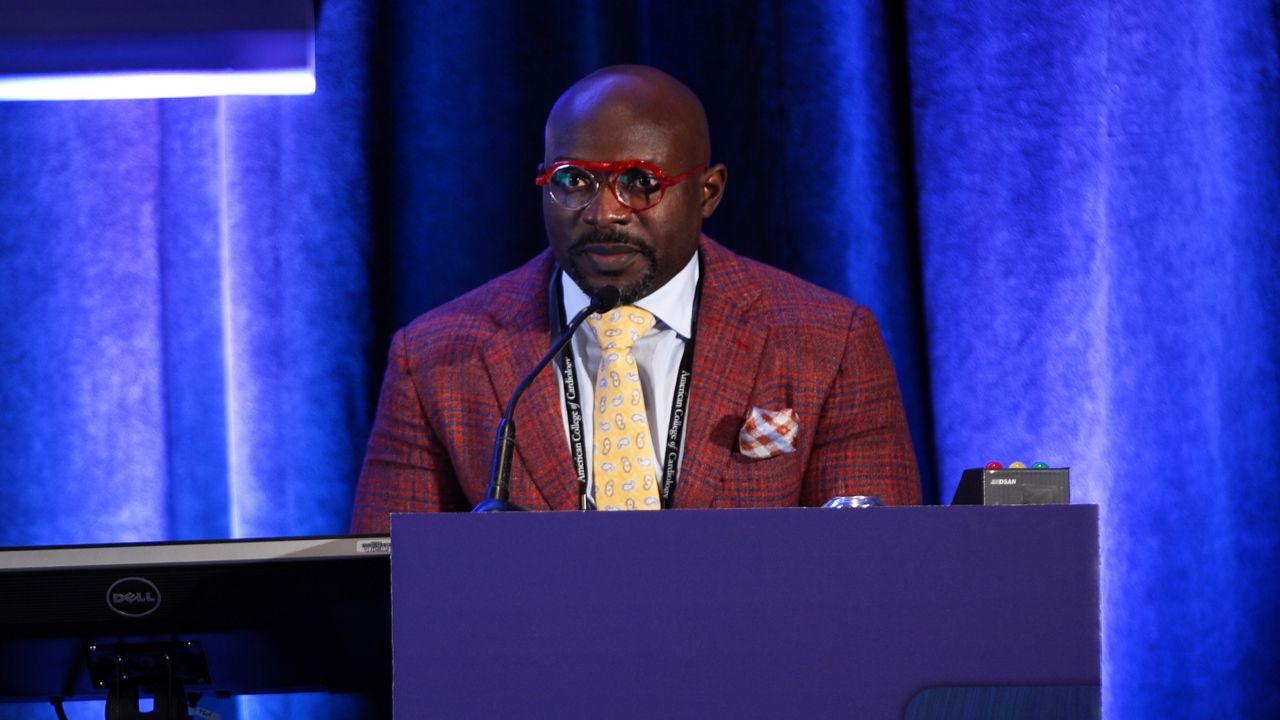

That’s a challenge doctors and patients on the frontlines of the diabetes crisis know all too well. Dr. Foluso Fakorede has been fighting for institutional changes for years.

Monday through Friday, Dr. Fakorede spends his days trying to prevent his patients from losing their limbs to peripheral artery disease — a condition often caused by uncontrolled diabetes. On the weekends, he shares their stories with anyone who will listen.

“We talk about raising awareness from a patient provider and community level. But policy and educating our, you know, our lawmakers is actually at the forefront.”

His advocacy has won him allies in Congress, including New Jersey Congressman Donald Payne Jr.

For Payne Jr., the diabetes crisis is personal. In March, 2022 he gave an impassioned speech on the House Floor, urging his colleagues to take action to help diabetics like him, who require insulin to survive. Standing at the podium, he pointed down to the medical boot he wore on one foot. “The boot that I’m wearing is not a fashion decision,” he told them. “It’s because I have a diabetic ulcer on my foot — the fourth one I’ve had in seven years.”

Payne has been fighting his own battle with diabetes for 30 years. He’s now on dialysis, and lives with many other complications, including heart disease and loss of feeling in his feet — the result of peripheral artery disease, or PAD.

It inspired him to create the PAD caucus in 2019, to raise awareness among his colleagues.

“They see their constituents that have lost limbs and, you know, trying to understand why. And so we're bringing that knowledge to Congress.”

Working with Fakorede, he has introduced legislation that would provide Medicare reimbursements for PAD screenings in at-risk patients with the goal of reducing amputations.

“That is what we need to do across the board,” says Fakorede. The current system, he believes, leaves too much of the burden with the patients.

And the burden of diabetes is not evenly distributed.

“We've seen that in spite of all the advancements in medicines in technology and advancements in care that we've seen in the healthcare field, the mortality rates for Black Americans have widened.”

Fakorede says the problem starts with how clinical research is conducted. Medical guidelines and policies, he points out, are made based on data. “Historically, less than five percent of African-Americans have been included in research trials.”

It’s an issue that Ruiz is working to address through a piece of legislation called the Diverse Clinical Trials Act, which aims to increase Black and brown representation in trials. In time, he hopes it will improve the accuracy of data and affect policy changes.

But Fakorede believes the crisis is evident, and action is needed now. “I've seen enough data. I've seen enough coffins. I've seen enough memorials. I've seen enough amputees. I've seen enough dialysis machines.”

He hopes that his advocacy will inspire others to work towards a solution.

“I think that we need more disruptive, positive ideas to move that needle. We need more changemakers across the spectrum.”

For more, watch Part 1 and Part 2 of Erin Billups’ and Errol Louis’ joint series on the nationwide diabetes crisis.