Orthopedic experts have long wanted a better way to fix torn ACLs, especially as the number of young athletes experiencing these injuries continues to rise. National Health Reporter Erin Billups takes a closer look at the latest advancement that may offer a better future to patients post surgery.

What You Need To Know

- The new procedure uses an FDA approved implant injected with the patient's blood

- The new method for ACL repairs may lead to faster and more complete recoveries from ACL tears

- It's estimated that more than 100,000 ACL repair surgeries are performed every year in the U.S.

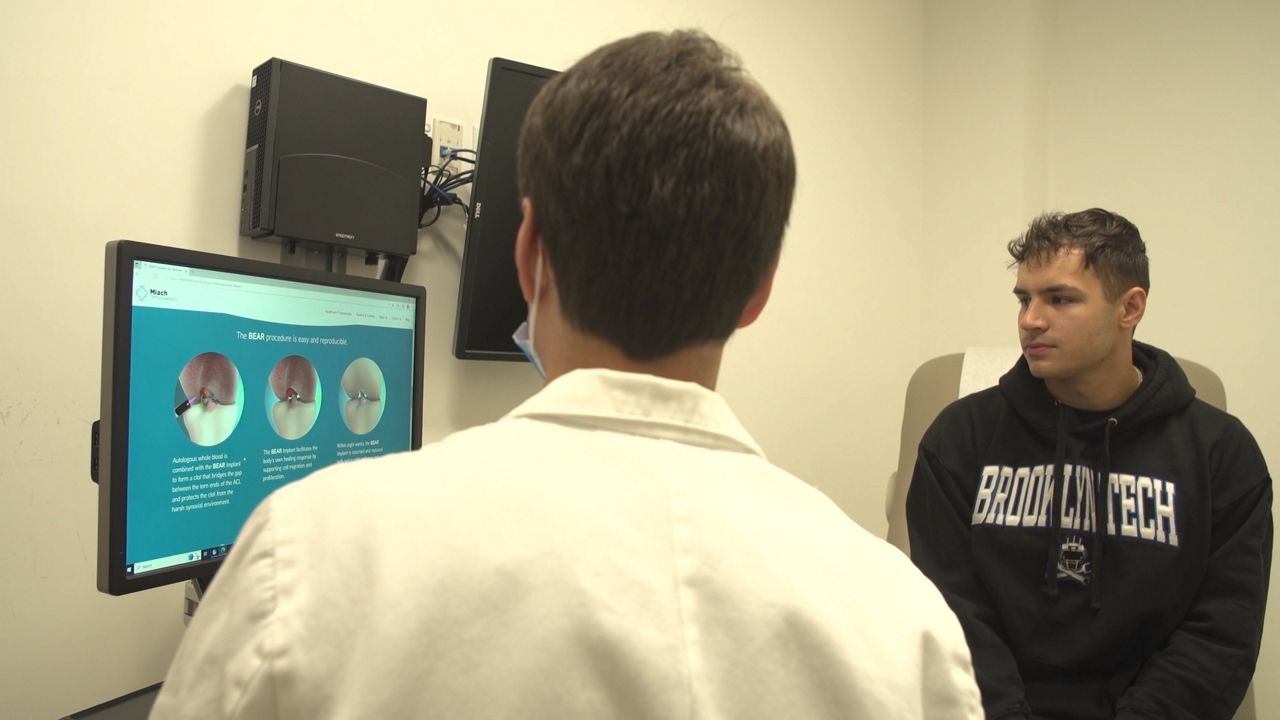

A torn ACL in Michael Marcovici’s right knee, followed by the COVID shutdown, ended his college football career before it began. A few years later, while playing in a collegiate rugby scrimmage, it happened again- this time to his left knee.

“I was just running and I made a cut and I guess my knee just gave out. I think I got stuck in the turf a bit, so my cleat got stuck, my knee twisted,” says Marcovici.

It’s a common injury for athletes. The ACL, or anterior cruciate ligament, stabilizes the knee, allowing for quick pivots or cuts. But overuse can lead to tears.

For years the solution has been to reconstruct the ligament. That is what Marcovici’s orthopedic surgeon, Dr. Shawn Anthony, performed on his right knee. A part of the patellar tendon was grafted from the front of the knee and anchored inside the knee, replacing the torn ACL.

“They kind of rerouted it and it acts as your ACL,” says Marcovici. “They scrape out all of your remaining ACL. So I technically don't have, like my native ACL.”

It is estimated more than 100,000 ACL reconstructions are performed each year in the U.S., with the number of ACL tears among teens increasing about 2.3 percent each year. With the exception of pandemic shutdown of sports.

Dr. Anthony is an orthopedic surgeon at Mount Sinai in New York City. He is among a team of specialists that regularly treat top-level athletes, most recently providing onsite care to players at this year’s U.S. Open tennis tournament. When Marcovici returned to him with his injured left knee, Anthony decided to try a new procedure, an ACL restoration, not a reconstruction.

“This new technique is a paradigm shift in that we're trying to use the patient's own tissue to heal itself and trying to mend the two torn edges of the ACL tissue back together,” says Anthony.

Fluid in the knee prevents blood from clotting and the ACL from healing on its own. The new procedure uses an FDA approved collagen scaffold called the Bridge enhanced ACL restoration – or BEAR implant to help the injury heal.

“It is loaded with the patient's own blood and it's interposed between the two torn edges of the ACL. And the implant itself dissolves in approximately two months,” says Anthony.

He says the hope is that the more natural healing process will lead to fewer issues down the road. That recovered patients will experience more natural biomechanics post surgery.

“We know that with traditional ACL reconstruction techniques that almost one in three patients will develop osteoarthritis or loss of cartilage in their knee within ten years of their injury,” says Anthony. “This is especially devastating for young patients in their teenage years because that means we're seeing a lot of patients in their twenties who already have knees with significant osteoarthritis.”

Anthony says more research is needed to determine exactly how much of the remaining ACL tissue is needed to successfully perform restoration surgeries. In the meantime, he says he wants to see more emphasis on ACL prevention programs, which offer young athletes better techniques to prevent tears from happening in the first place.

“There's a variety of things that are proven to reduce ACL injury rates in youth. One is participating in multiple sports as opposed to early sport specialization. And the second, there are very clear evidence based ACL prevention programs,” says Anthony. “Learning to jump the right way, land the proper way, strengthening core quad hip muscles to help protect the ACL.”

Marcovici felt the difference between the two ACL repair procedures right away after the surgery on his left knee.

“I would definitely say my right knee hurt a lot more,” says Marcovici. “I wouldn't kneel or do lunges or things like that early on for my right knee, which I've been capable of doing for my left knee. So that's like an immediate difference.”

Anthony says often, less pain medication is needed after the BEAR implant surgery. “It's a more minimally invasive procedure without needing to drill big tunnels in the bone like we do for traditional ACL reconstruction.”

Marcovici says one downside is the length of recovery time. It takes just as long, if not longer, for the body to heal itself with the collagen scaffold. All ACL repair procedures require 10 to 12 months of physical therapy to regain neuromuscular control.

While Marcovici says he dislikes the length of rehab, he’s hoping the implant was the right thing for him, because he plans on living an active, athletic life.

“I think it'll be better for me in the long run,” says Marcovici. “I'll thank myself for it, like, when I'm 50.”