The world’s widest glacier is at risk of rapidly retreating in the “near future,” a process that could raise global sea levels to concerning heights, according to a study published in the journal Nature Geoscience on Monday.

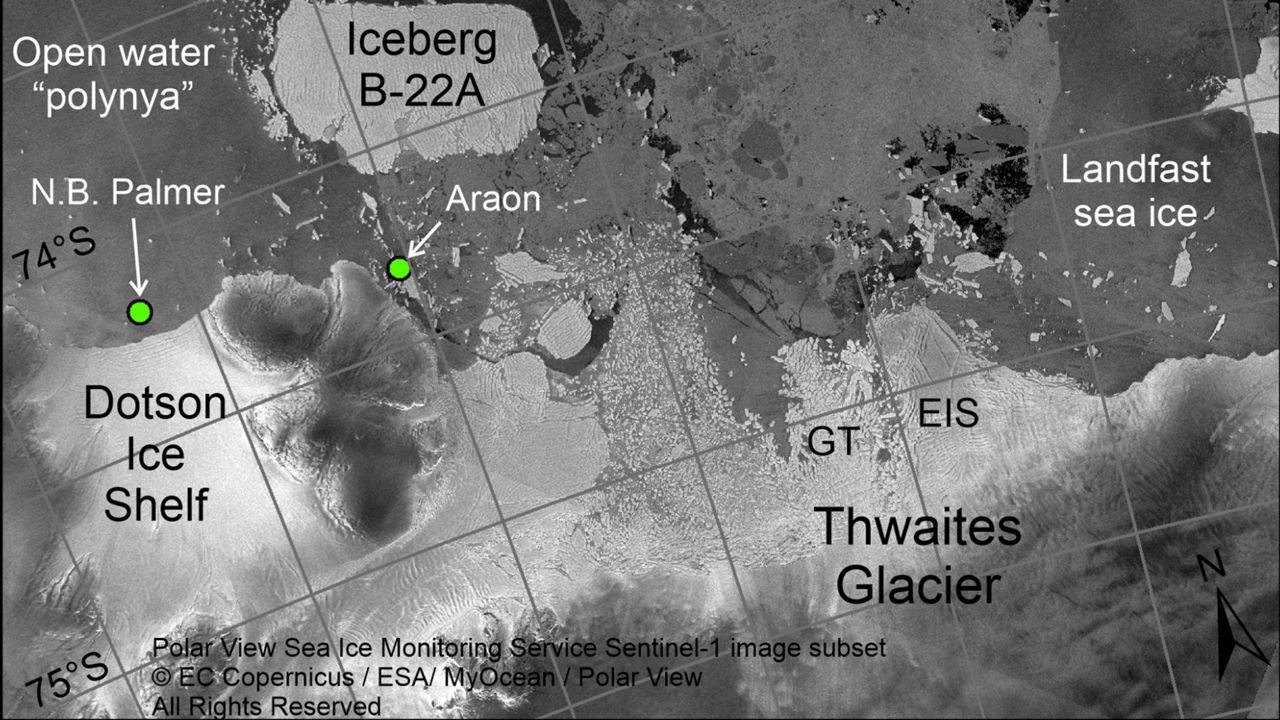

The massive but melting Thwaites glacier rests on Antarctica’s western half, east of the jutting Antarctic Peninsula. The Florida-sized glacier has gotten the nickname the “doomsday glacier” because of how much ice it has and how much seas could rise if it all melts.

According to research published Monday, the glacier could soon experience a rapid melting period, meaning that sea rise could come sooner – and in a much shorter timespan – than previously thought.

Led by researchers at the University of South Florida, scientists used an autonomous underwater vehicle to examine the imprints left on the ocean floor by the glacier when it retreated in previous years. Because much of the Thwaites glacier is underwater and near the ocean floor, it is particularly susceptible to warming ocean currents that melt it from below.

The edge of the Thwaites rests on a “grounding zone,” or the location where the glacier lifts off from the ocean floor and floats freely as an ice shelf. When warm water goes underneath the ice shelf and toward the grounding zone, it slowly eats away at the bottom of the glacial ice, which can eventually cause ice to break off or re-shift along the ocean floor. Scientists can examine the indentations left in the ocean floor to determine when glaciers may have experienced rapid periods of melting in the past and how quickly the processes happened.

By examining 160 ridges – or “ribs” – along the seafloor, scientists discovered that the Thwaites is actually retreating at a slower pace, on average, than it has in recent years. But they also discovered that at some point in the past two centuries, the glacier retreated at a rate of 1.3 miles a year in a span of under six months, twice as far as the glacier retreated between 1996 - 2009 and three times farther than between 2011 - 2017.

Because the retreating glacier could only be examined by satellite imaging until the last several decades, scientists are not yet sure exactly when that rapid change occurred – but posit it “almost certainly pre-date[s] the 1950s,” though it could be much older should they discover periods of slower retreat.

But experts from the University of South Florida and elsewhere are worried another quick retreat is on the horizon for the Thwaites, which currently rests on seafloor ridges that act as a sort of barrier to the submerged ice.

“Thwaites is really holding on today by its fingernails, and we should expect to see big changes over small timescales in the future – even from one year to the next – once the glacier retreats beyond a shallow ridge in its bed,” study co-author, Robert Larter of the British Antarctic Survey, wrote in a statement.

Should the Thwaites melt entirely, scientists describe the situation as “bone-chilling,” saying global water levels could rise anywhere from three to 10 feet should the glacier and its surrounding ice fields disappear.

There are several characteristics of the Thwaites that make scientists particularly concerned about its collapse, which appears to be occurring in three ways, one of which is the melting from below by ocean water.

The land part of the glacier is also “losing its grip” to the place it attaches to the seabed, so a large chunk can come off into the ocean and later melt, Oregon State University ice scientist Erin Pettit said earlier this year.

Finally, the glacier’s ice shelf is breaking into hundreds of fractures like a damaged car windshield. This is what Pettit said she fears will be the most troublesome with six-mile (10-kilometer) long cracks forming in just a year.

As all of these factors work towards “thinning and progressive grounding-line retreat at Thwaites Glacier,” the chances that a rapid pulse retreat could occur in the “coming decades” increase, experts wrote Monday.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.