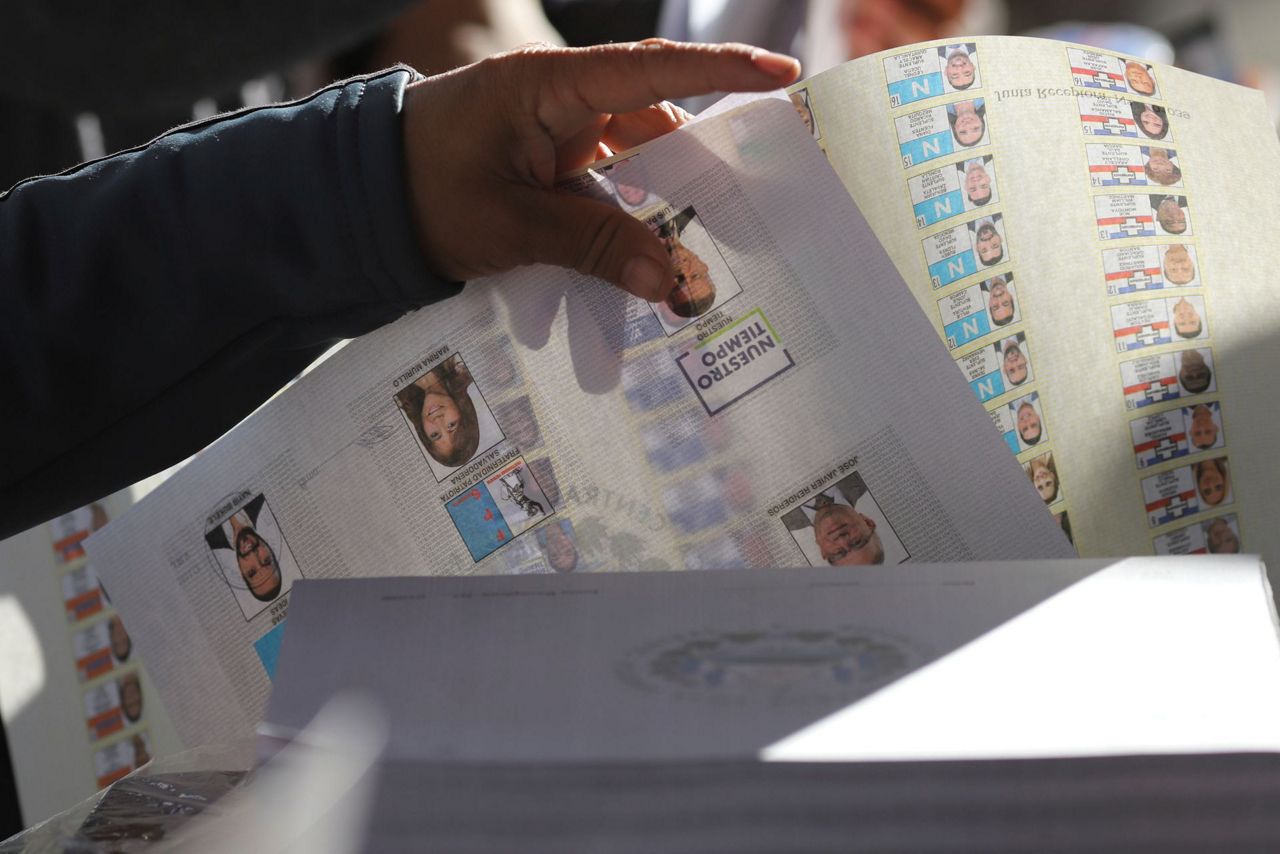

SAN SALVADOR, El Salvador (AP) — Salvadorans voted in presidential and legislative elections Sunday, with many expressing willingness to forego some elements of democracy if it means keeping gang violence at bay.

With soaring approval ratings and virtually no competition, Nayib Bukele was almost certainly headed for a second 5-year term as president. After voting, he jousted with reporters, asserting that the election's results would serve as a “referendum” on his administration.

Polling places closed at 5 p.m., though people still in line were allowed to cast their ballots. Judging by previous elections, some preliminary results were expected late Sunday.

El Salvador’s constitution prohibits reelection. Nonetheless, about eight out of 10 voters support Bukele, according to a January poll from the University of Central America. That's despite Bukele taking steps throughout his first term that lawyers and critics say chip away at the country's system of checks and balances.

After his party was victorious in 2021 legislative elections, the newly elected congress purged the country’s constitutional court, replacing judges with loyalists. They later ruled that Bukele could run for a second term despite the constitutional ban on reelection.

Bukele's administration has arrested more than 76,000 people since a gang crackdown began in March 2022. The massive arrests have been criticized for a lack of due process, but Salvadorans have retaken their neighborhoods long controlled by gangs.

José Dionisio Serrano, 60, was proud to be the first person in line at 6 a.m. Sunday as voters started to wait outside a school in the formerly gang-controlled neighborhood of Zacamil in Mejicanos just north of San Salvador. The soccer teacher said he planned to vote for Bukele and his party New Ideas.

“We need to keep changing, transforming,” Serrano said. “Honestly, we have lived through very hard periods in my life. As a citizen I have lived through periods of war, and this situation we had with the gangs. Now we have a big opportunity for our country. I want the generations that are coming up to live in a better world.”

Mejicanos was historically divided between two gangs most of Serrano's life, and he had to flee for several years after gang members shot him and threatened his life. Asked about concerns that Bukele was seeking reelection despite a constitutional ban, he brushed it aside, saying, “What the people want is something else.”

El Salvador's traditional parties from the left and right that created the vacuum that Bukele first filled in 2019 remain in shambles. Alternating in power for some three decades, the conservative Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA) and leftist Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) were thoroughly discredited by their own corruption and ineffectiveness. Their presidential candidates this year were polling in the low single digits.

“There's a disconnect between the people and the political parties as a political structure,” said Joao Picardo, a researcher at Francisco Gavidia University. Salvadorans say they have “connected more with the figure of the president.”

Bukele, the self-described “world’s coolest dictator,” has gained fame for his brutal crackdown on gangs, in which more than 1% of the country’s population has been arrested.

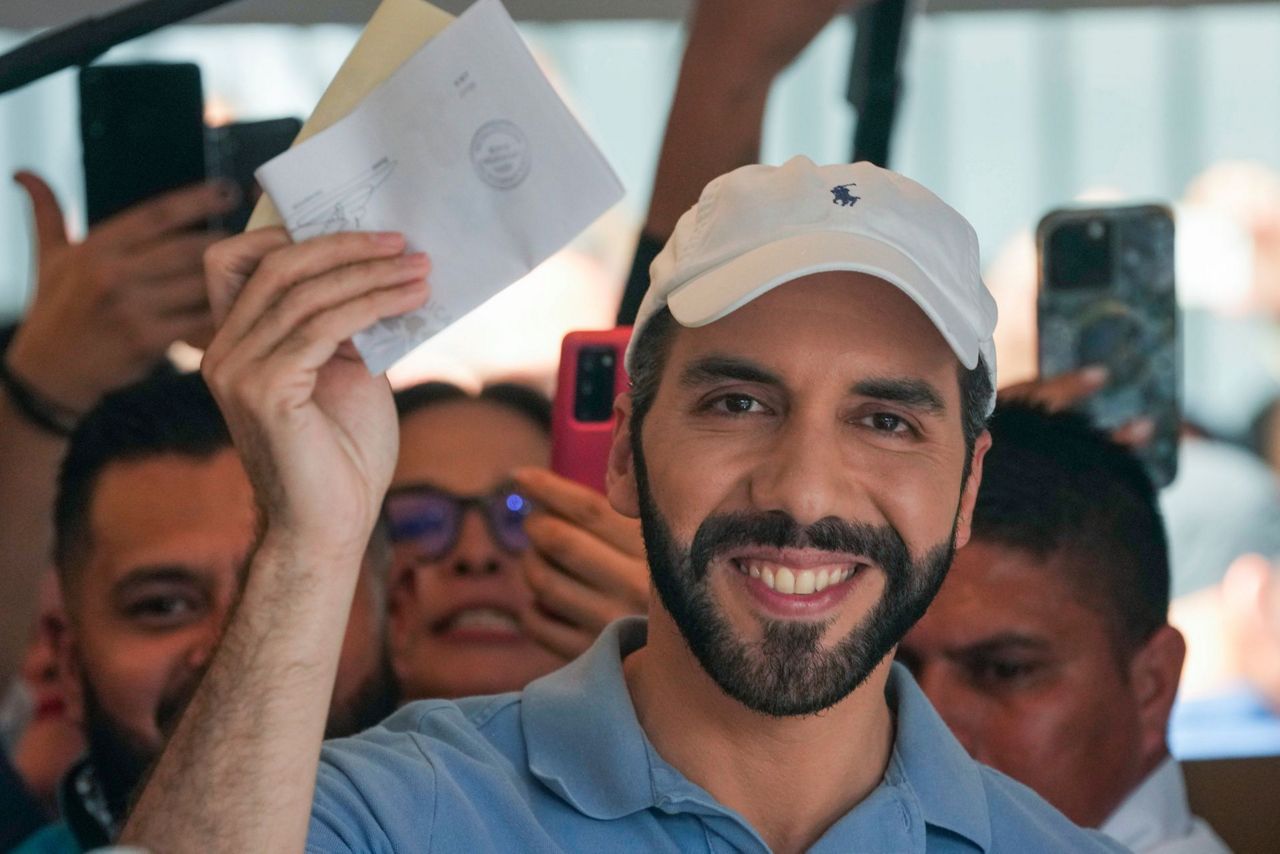

On Sunday afternoon, Bukele waded through a crowd of supporters to vote wearing a blue golf shirt and white baseball cap.

Smiling, Bukele and his wife dropped their ballots into the box as R.E.M.'s 1987 hit “It’s the End of the World as We Know It (And I Feel Fine),” blared over speakers. Bukele has a habit of trolling his critics.

Shortly after casting his vote, Bukele said at a news conference that it was important to elect a Legislative Assembly that will continue approving the state of emergency that has given him extraordinary powers to combat the gangs.

Bukele said the vote could be seen as a “referendum” on what his administration had done.

“We are not substituting democracy because El Salvador never had democracy," he said. “This is the first time in history that El Salvador has democracy. And I'm not saying it, the people say it.”

Asked about innocents swept up in the gang crackdown, he said El Salvador had one of the world's highest incarceration rates now because it is moving from being the world's murder capital to being one of its safest countries. He dismissed foreign criticism as promoting failed “recipes” and ignoring his administration's homegrown solution.

While his administration is accused of committing widespread human rights abuses, violence has also plummeted in a country known just a few years ago as one of the most dangerous in the world.

Because of that, voters like 55-year-old businesswoman Marleny Mena are willing to overlook concerns that Bukele has taken undemocratic steps to concentrate his power.

Formerly a street vendor in San Salvador's once gang-controlled downtown, Mena said she used to be scared to walk around the city, fearful she could accidentally cross from one gang's territory to another, with potentially serious consequences. Since Bukele began his crackdown, that fear has dissipated.

"He just needs a little bit more time, the time he needs to keep improving the country,” Mena said.

Though critics like Reinaldo Duarte, an informal worker who sells books in the street, said he would vote for FMLN, not because they could win, but to vote against Bukele.

He said the stalled economy has disproportionately affected informal workers, and expressed concern that Bukele’s government is not transparent in its management of public funds and its war on the gangs, saying “there are a lot of free gang leaders.”

Duarte's criticism was echoed by opposition politicians like Claudia Ortiz, of the party VAMOS, who urged voters to support candidates outside of Bukele's party in the legislative elections in order to preserve checks and balances.

“Absolute power corrupts absolutely,” she said in a video recorded from polling stations. “When all of the power is in the hands of just one group, just one party, it's easier for them to steal, it's easier for them to lie, for them to say they're doing things they are not actually doing.”

In the lead-up to Sunday’s vote, Bukele made no public campaign appearances. Instead, the populist plastered his social media and television screens across the country with a simple message recorded from his couch: If he and his New Ideas party didn’t win elections this year, the “war with the gangs would be put at risk.” He placed a special emphasis on legislative elections, key to the leader pushing through his agenda.

“The opposition will be able to achieve its true and only plan, to free the gang members and use them to return to power,” he said.

The 42-year-old Bukele and his party are increasingly looked to as a case study for a wider global rise in authoritarianism.

“There’s this growing rejection of the basic principles of democracy and human rights, and support for authoritarian populism among people who feel that, concepts like democracy and human rights and due process have failed them,” said Tyler Mattiace, Americas researcher for Human Rights Watch.

___

Alemán reported from Santa Tecla, El Salvador.

Copyright 2024 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.