NEW YORK (AP) — Former President Donald Trump returned to his civil fraud trial Thursday to spotlight his defense, renewing his complaints that the case is baseless and heaping praise on an accounting professor's testimony that backed him up.

With testimony winding down after more than two months, the Republican 2024 presidential front-runner showed up to watch New York University accounting professor Eli Bartov.

The academic disputed the crux of New York State Attorney General Letitia James' lawsuit: that Trump's financial statements were filled with fraudulently inflated asset values for such signature assets as his Trump Tower penthouse and his Mar-a-Lago club in Florida.

“My main finding is that there is no evidence whatsoever of any accounting fraud,” said Bartov, whom Trump's lawyers hired to give expert perspective. Trump’s financial statements, he said, “were not materially misstated.”

He suggested that anything problematic — like a huge year-to-year leap in the estimated value of the Trump Tower triplex — was simply an error.

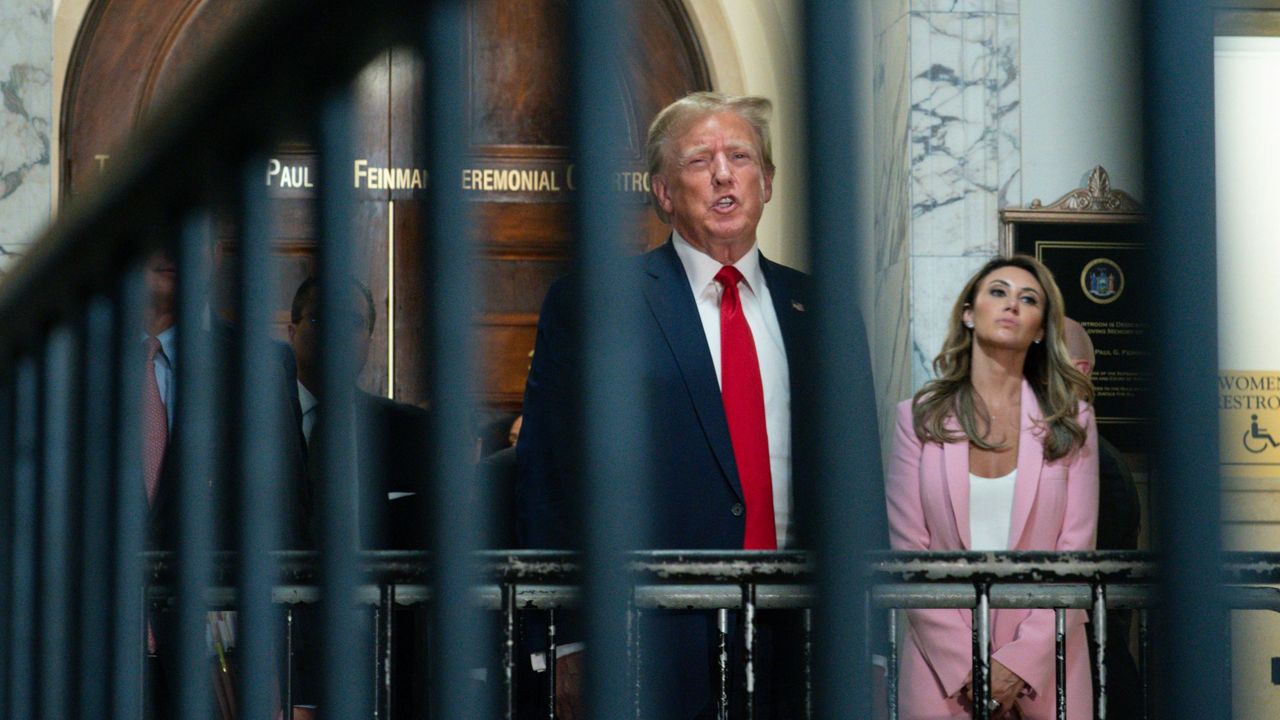

Even while campaigning to reclaim the presidency and fighting four criminal cases, Trump is devoting a lot of attention to the New York trial. He’s been a frustrated onlooker, a confrontational witness and a heated commentator outside the courtroom door.

Earlier in the trial, Trump attended several days and spent one on the witness stand while the state was presenting its case. But Thursday marked his first appearance since the defense began calling its own witnesses. He’s due to testify again Monday.

He watched keenly Thursday, pointing out documents to his lawyers and at points slapping the defense table or shaking his head over objections to some of Bartov's testimony. During breaks, Trump lauded the witness and assailed the lawsuit, which is putting his net worth on trial and threatens to disrupt the real estate empire that vaulted him to fame and the White House.

“This is a case that should have never been brought," Trump declared as he left for the day, calling the trial “a witch hunt,” “election interference” and "a disgrace to America.”

James' lawsuit accuses Trump, his company and top executives including his sons Eric and Donald Trump Jr. of misleading banks and insurers by giving them financial statements that padded his net worth by billions of dollars.

The statements were provided to help secure deals, including loans at attractive interest rates available to hyperwealthy people. Some loans required updated statements each year.

Trump denies any wrongdoing, and he posits that the statements' numbers actually fell short of his wealth. He has downplayed the documents' importance in dealmaking, saying it was clear that lenders and others should do their own analyses. And he claims the case is a partisan abuse of power by James and Judge Arthur Engoron, both Democrats.

Bartov testified that financial statements are just starting points for lenders, and that the documents' value estimates are inherently subjective opinions. Differences in such opinions don't mean that there's fraud, the professor said.

He called Trump's financial statements transparent and uncommonly detailed, with caveats that Bartov claimed “even my 9-year-old granddaughter” would understand. So did major Trump lender Deutsche Bank, Bartov maintained.

Deutsche Bank executives have testified that, while expecting clients to provide broadly accurate information, they often adjust the numbers. Internal bank documents pegged Trump’s net worth substantially lower than his financial statements did.

But if the bank adjusted the figures that Trump reported, “what if the reported values are incorrect?” the judge asked Bartov. He responded that the bankers didn't necessarily work from Trump's original numbers.

“So then why get them in the first place?” Engoron asked.

Noting that the figures came with pages of notes, Bartov said the package “allowed them to compute the numbers on their own.”

State lawyer Kevin Wallace repeatedly complained that Bartov's opinions on Deutsche Bank's approach strayed beyond his expertise, at one point calling him “someone who’s hired to say whatever they want in this case.”

“You should be ashamed of yourself, talking to me like that!” Bartov exclaimed. “I am here to tell the truth.”

The attorney general’s office has also hired Bartov as an expert in the past.

Trump has regularly railed about the case on his Truth Social platform. But going to court in person affords him a microphone — in fact, many of them, on the news cameras positioned in the hallway. He often stops to expostulate on his way into and out of the courtroom proceedings, which cameras can’t record.

His out-of-court remarks got him fined $10,000 Oct. 26, when Engoron decided Trump had violated a gag order that prohibits participants in the trial from commenting publicly on court staffers. Trump's lawyers are appealing the gag order.

James hasn't let Trump go unanswered.

“Here’s a fact: Donald Trump has engaged in years of financial fraud. Here’s another fact: When you break the law, there are consequences,” James’ office wrote this week on X, formerly Twitter.

The attorney general herself has often come to court when Trump is there, though she didn’t Thursday.

While the non-jury trial is airing claims of conspiracy, insurance fraud and falsifying business records, Engoron ruled beforehand that Trump and other defendants engaged in fraud. He ordered that a receiver take control of some of Trump’s properties, but an appellate court has held off on that order. The pause was extended indefinitely Thursday for the appeals process to play out, a development that Trump celebrated.

At trial, James is seeking more than $300 million in penalties and a prohibition on Trump and other defendants doing business in New York.

Testimony is expected to conclude before Christmas. Closing arguments are scheduled in January, and Engoron is aiming for a decision by the end of that month.

__

Associated Press journalist Joseph Frederick contributed to this report.

Copyright 2023 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.