NAIROBI, Kenya (AP) — The graves at the edge of the orphanage tell a story of despair. The rough planks in the cracked earth are painted with the names of children, most of them dead in the 1990s. That was before the HIV drugs arrived.

Today, the orphanage in Kenya’s capital is a happier, more hopeful place for children with HIV. But a political fight taking place in the United States is threatening the program that helps to keep them and millions of others around the world alive.

The reason for the threat? Abortion.

The AIDS epidemic has killed more than 40 million people since the first recorded cases in 1981, tripling child mortality and carving decades off life expectancy in the hardest-hit areas of Africa, where the cost of treatment put it out of reach. Horrified, then-President George W. Bush and the U.S. Congress two decades ago created what is described as the largest commitment by any nation to combat a single disease.

The program, known as the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, or PEPFAR, partners with nonprofit groups to provide HIV/AIDS medication to millions around the world. It strengthens local and national health care systems, cares for children orphaned by AIDS and provides job training for people at risk.

Now, a few Republican lawmakers are endangering the stability of the program, which officials say has saved 25 million lives in 55 countries from Ukraine to Brazil to Indonesia. That includes the lives of 5.5 million infants born HIV-free.

At the Catholic-run Nairobi orphanage, program manager Paul Mulongo has a message for Washington.

“Let them know that the lives of these children we are taking care of are purely in their hands," Mulongo says.

The issue of abortion has been a sensitive one since PEPFAR's inception in 2003. But each time the program came up for renewal in Congress, Republicans and Democrats were able to put aside partisan politics to support a program that's long been seen as the vanguard of global aid.

“Most eras in countries are measured by loss of life in war and famine and pandemic,” said Tom Hart, president of the ONE Campaign, a nonpartisan organization that worked with Bush, a Republican, to create the program. “This era has been measured in lives saved.” The campaign has published a letter from dozens of faith leaders to Congress calling PEPFAR “a story of medical miracles and mercy.”

But the bipartisan support is cracking as the program is set to expire at the end of September. The trouble began in the spring, when the Heritage Foundation, an influential conservative Washington think tank, accused the Biden administration of using PEPFAR “to promote its domestic radical social agenda overseas.”

The group pointed to new State Department language that called for PEPFAR to partner with organizations that advocate for “institutional reforms in law and policy regarding sexual, reproductive and economic rights of women.” Conservatives argued that's code for trying to integrate abortion with HIV/AIDS prevention, a claim the administration has denied.

In language echoing the early, harsh years of the epidemic, Heritage called HIV/AIDS a “lifestyle disease” that should be suppressed by “education, moral suasion and legal sanctions.” It recommended halving U.S. funding for PEPFAR, saying poor countries should bear more of the costs.

Shortly after that, U.S. Rep. Chris Smith, a longtime supporter of PEPFAR who wrote the bill reauthorizing it in 2018, said he would not move forward with reauthorization this time unless it barred nongovernmental organizations that used any funding to provide or promote abortion services. He said he came to this decision after having extensive conversations with stakeholders involved.

And the threat from the New Jersey Republican comes with weight: He chairs the U.S. House Foreign Affairs subcommittee with jurisdiction over the program’s funding.

Because that proposal faces stiff opposition from congressional Democrats, Smith, with support from prominent anti-abortion groups, wants to cut PEPFAR’s usual five-year funding to one year if that ban is not included. He said that way the program would remain funded at its highest level — $6.7 billion — while allowing lawmakers to annually to revisit contracts with partners they believe may support or provide abortion services.

The proposal would also include a measure that requires at least 10% of funds to be directed to NGOs like the Nairobi orphanage, which targets orphans and vulnerable children affected by HIV/AIDS.

“It’s a false narrative that says that you can’t do (the program) year by year as we try to protect the unborn child,” Smith told The Associated Press.

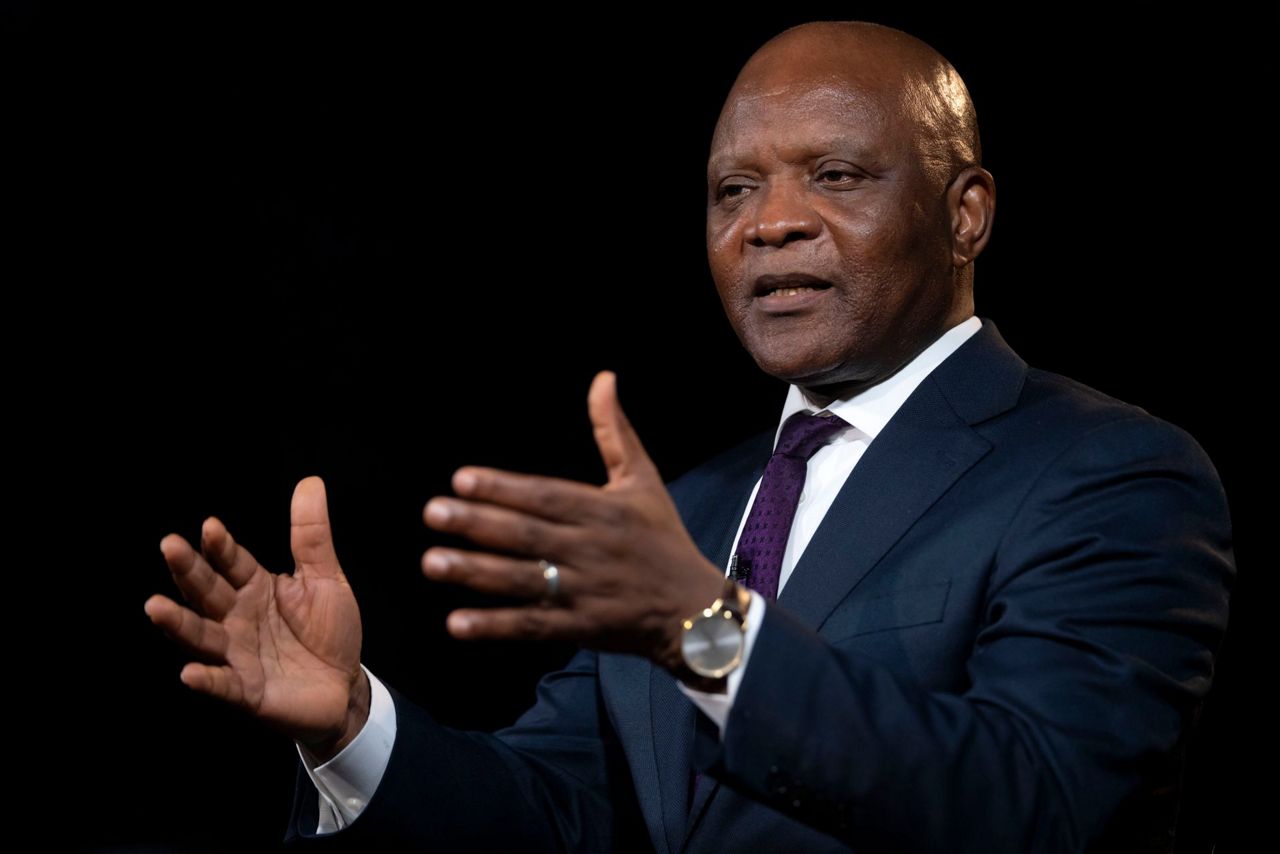

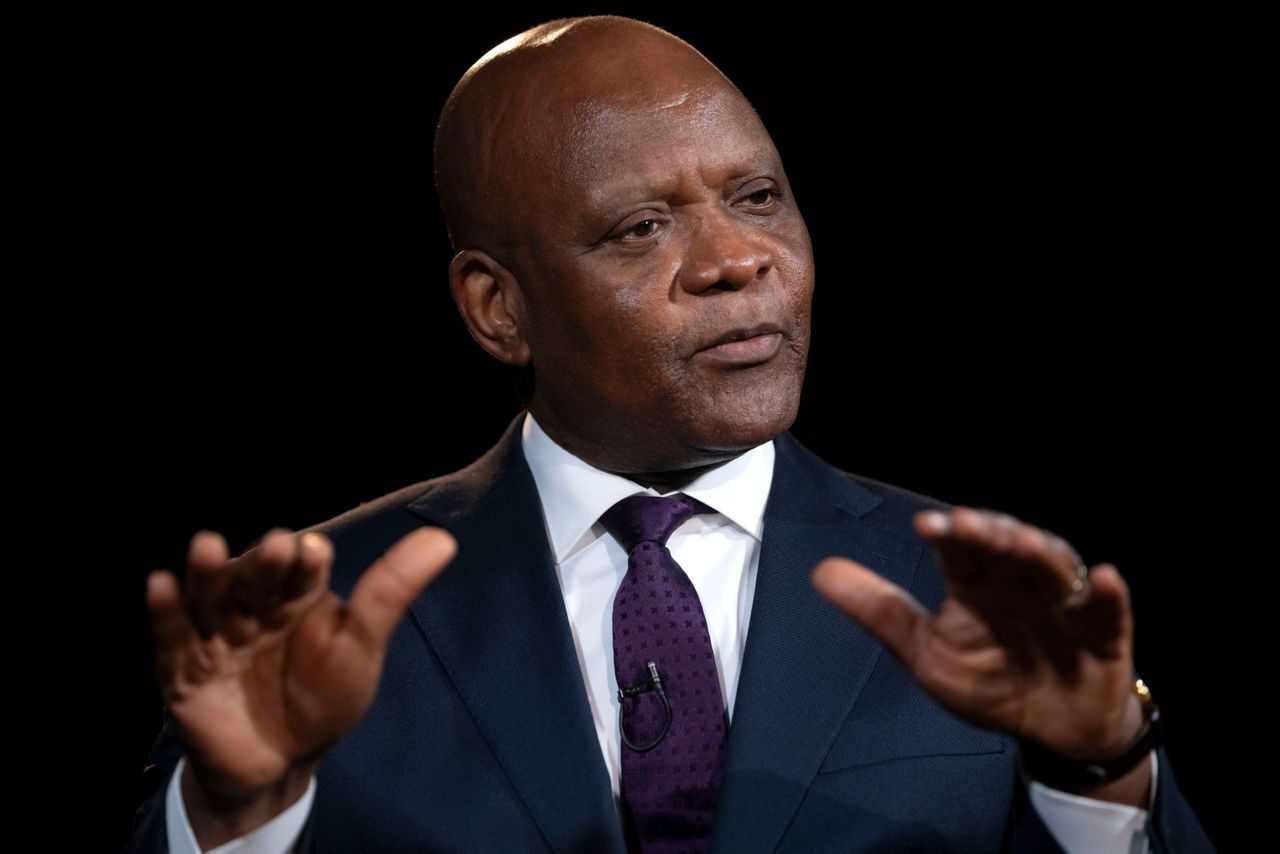

But supporters of the program say that under existing U.S. law, partners are already prohibited from using its funding for abortion services. The head of PEPFAR, John Nkengasong, told the AP he knew of no instance of the program’s money going directly or indirectly to fund abortion services.

He warned that any instability in the flow of U.S. funding for PEPFAR could have dangerous implications for health globally, including in the United States. The key to controlling AIDS, he said, is the assurance that infected people have a pill to take each day.

Without that, the virus could come back, ”and about 20 million lives might be lost in the coming years,” he said. “The fragile gains that we’ve achieved will be lost.”

In Africa, many PEPFAR partners and recipients in largely conservative countries don’t support abortion either because of religious beliefs. But the idea that the program reliant on the steady supply of HIV drugs could be subject to political winds is a cause for alarm.

“If PEPFAR goes, who is going to meet that cost?” asked Josephine Kaleebi, who leads an organization in Uganda that helped the program's first-ever recipient of HIV treatment medication.

“We are proud to say that the first recipient is alive,” Kaleebi said.

The group, Reach Out Mbuya Community Health Initiative, was founded by members of Uganda’s Catholic Church, which is against abortion. In the reception area, portraits of priests line the walls.

But Reach Out helps anyone who walks in needing HIV drugs, Kaleebi said. About 6,000 people are served, many of them “the extremely most vulnerable” from one of the poorest areas of the capital, Kampala.

Mark Dybul, who helped create and lead PEPFAR under Bush, warned that weakening PEPFAR would also hurt the diplomatic goodwill the U.S. has created in developing regions.

“It’s no secret that we are in a geopolitical struggle for influence in Africa with Russia and China,” he said. “And our biggest influence in many ways, visible and most impactful, is PEPFAR.” A spokesperson for former president Bush declined comment.

In neighboring Kenya, Bernard Mwololo believes he is alive because of the drugs that PEPFAR provides. “Sometimes it’s so crazy when you hear people saying that these HIV drugs should be bought by the local government,” he said. “I am telling you, they can’t manage it.”

The 36-year-old, now an HIV activist, has lived most of his life at the Nairobi orphanage after his parents died of AIDS. He recalled arriving and learning that he could have hope. He was enrolled in a better school, was given a bicycle and ate balanced meals.

The number of children in sub-Saharan Africa newly orphaned by AIDS reached a peak of 1.6 million in 2004, the year that PEPFAR began its rollout of HIV drugs, researchers wrote in a defense of the program published by The Lancet medical journal last month. In 2021, the number of new orphans had dropped to 382,000.

Deaths of infants and young children from AIDS in the region have dropped by 80%.

Now the orphanage is transformed. Children dart around playing soccer or swing in the colorful play area. Some are among the 1.4 million children and adults living with HIV in Kenya, according to UNAIDS. More than 1 million have received free HIV drugs because of PEPFAR.

Stopping PEPFAR would be like committing “global genocide,” said Mulongo, the orphanage program manager.

He recalled how helpless he felt watching children die before HIV drugs were readily available. Almost two decades ago, they would lose at least 30 children a month to AIDS.

Elsewhere in Nairobi, 16-year-old Idah Musimbi is part of a generation that has grown up without the fear that an HIV diagnosis was a likely death sentence.

She displayed the pills that have given her a sense of normalcy. She contracted HIV at birth.

“I don’t think I would live for long if these drugs stopped coming. My grandparents cannot afford to buy food every day, let alone these ARVs,” she said.

Her grandfather David Shitika, a pastor, said he owes the lives of his granddaughter and her mother to PEPFAR. His daughter was diagnosed with HIV in 1995, when many people were dying.

“It was called the slimming killer disease,” he said. “Nobody wanted to live with an infected person, and those who died were wrapped in nylon bags before burial” for fear of infection.

Now he hopes that the Republicans' threat to PEPFAR will fade, and that his granddaughter will go on to study law and achieve her dream of becoming a judge.

“I want to tell the American people, God bless you,” Shitika said. “I do not know why you decided to help us.”

___

Amiri and Knickmeyer reported from Washington. Associated Press writer Rodney Muhumuza in Kampala, Uganda, contributed to this report.

Copyright 2023 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.