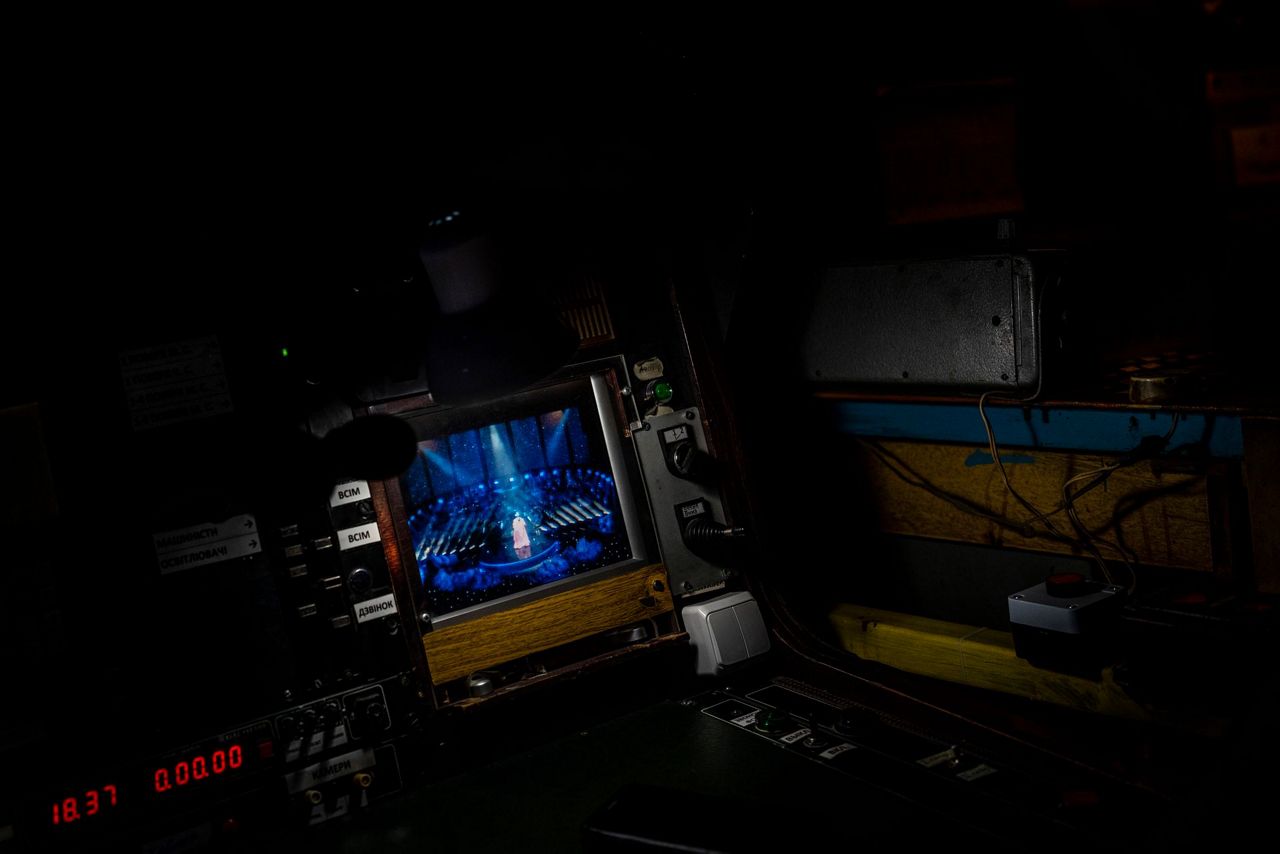

LONDON (AP) — Jamala and the orchestra were supposed be onstage, but they were sheltering in a basement.

Warnings of shelling and missile attacks had them below ground at the Kyiv Opera House instead of getting ready to perform for an audience.

The Ukrainian singer was at the venue to debut a selection of songs from her new album “Qirim” — a collection of Crimean Tatar tracks that was years in the making.

Musicians, sound engineers and lighting technicians were sheltering with her, waiting for the air raid threat to pass.

“It’s not normal, but, you know, it’s our life. It’s our everyday life in Kyiv,” Jamala said, speaking in the U.K. the following week.

And the show did go on, if a little late.

“For me, it was really important sign for the whole world that despite of everything, we are fighting our front-line war, (for) our culture, our heritage, for our history,” she said of the concert in Kyiv on Friday.

“Qirim” expands on the connection Jamala felt with her heritage when she performed a song about her ancestors at the 2016 Eurovision Song Contest. She won the competition that year in Stockholm with “1944,” which is about the deportation of Crimean Tartars by Soviet dictator Josef Stalin.

In May of that year, nearly 200,000 Crimean Tatars — who at the time accounted for about a third of the Crimean population — were deported to the steppes of Central Asia, 3,200 kilometers (2,000 miles) to the east. Stalin had accused them of collaborating with the Nazis — a claim widely dismissed as false by historians. An estimated half of them died in the next 18 months of hunger and harsh conditions.

While lot of groups sing in English at Eurovision in hopes of reaching a bigger audience, Jamala took the top prize by singing in a foreign language that would be familiar in only small pockets of the world.

“It was for the very first time that the world had listened (to) Crimean Tatar language. And all (the) Turkic world was so happy because it was the first time the Turkic language won in Eurovision,” she recalled.

She had been warned that the song was too dramatic, that audiences wouldn't connect with the pain of the deportation or with her family's history.

“But I said, ‘No, if people feel that it’s true, that they feel it’s so pure and honest, they believe me.’ And it happened.”

A similar pursuit of purity drove the album that is set for release this week.

Jamala dove deeper into the customs of her ancestors, looking for songs to represent different areas of the Crimean Peninsula, which Russia seized from Ukraine in 2014 in a move that most of the world regards as illegal.

She became part detective, part music historian as she puzzled together melodies and stories from folklore.

“I didn’t expect to find these treasures when I started this project,” she said. “It’s like a diary, very personal stories.”

One of the characters on the album is Alim Aidadmakh, a Robin Hood-type figure who fought injustice and stood up for the poor.

His story nearly wasn’t told at all. All the recordings, including Jamala's vocals and the musicians' tracks, were thought to have been lost in Kyiv after Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine early last year.

Luckily, sound producer Sergei Krutsenko was able to rescue the work of the more than 80 musicians who had worked virtually from all over the region in 2021, to bring the 14 tunes that make up “Qirim” to life.

After decades of dedication to this project and the near miss, how does Jamala feel now it’s available for people to listen to?

“I’m happy because it’s happened, because it’s really hard work with the whole team. But I’m sad because even in Crimea, you can’t listen this streaming because it’s banned. Because Crimea is still occupied by Russia.”

The singer spoke to The Associated Press from Liverpool while rehearsing to perform the album in its entirety for the first time with the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra, as part of this year’s Eurovision celebrations.

Ukrainian band Kalush Orchestra won last year's song contest, which gave Ukraine the right to host this year's competition. Because of Russia's war, that was deemed unsafe and the U.K. is hosting the event instead.

Ahead of Saturday's final, Jamala dismissed the idea that politics influences how judges and the public vote at Eurovision, suggesting that it’s more about emotion.

“If people feel this sympathy to you,” she says. “They (are) going to vote for you.”

And she still believes deeply in the importance of the international contest.

“For us, it’s a huge opportunity to say again and again, people listen. We are fighting for our freedom, for our rights to live in our home, to sleep in our beds, listen to us,” Jamala explains.

“And for everyone, for every country, it’s really the only one contest in the world, honestly, when you can show through the three minutes - it’s only three minutes — you can show your culture, your thoughts, your stories, everything. It’s magic.”

Copyright 2023 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.