OSORNO, Chile (AP) — In labor with her first child last month, Lucia Hernández Rumian danced around her hospital room while her husband played the kultrun, a ritual drum.

She turned down pain medication from the hospital’s staff to get massages and oil rubdowns instead from her cultural liaison, who had ceremonially purified the space according to Mapuche customs.

“It became my own space,” Hernández said.

The largest public hospital in the southern Chilean city of Osorno is finding new ways to incorporate these and other Indigenous health care practices. There's a special delivery room with Native images on the walls and bed, forms for doctors to approve herbal treatments from trusted traditional healers, and protocols for “good dying” mindful of spiritual beliefs.

The hospital’s efforts validate cultural practices at a time when Chile’s Indigenous groups — particularly its largest, the Mapuche — are fighting for rights and restitutions with unprecedented visibility as the country gets ready to vote on a new constitution next month.

But they also restore a crucial spiritual component to health care, according to health professionals and patients at Hospital Base San José de Osorno.

“It must be a guarantee – we take charge of the physical part, but without transgressing on the spiritual dimension,” said Cristina Muñoz, the certified nurse-midwife who launched new delivery protocols that Indigenous pregnant women can customize and are believed to be the first in the country.

Cristina Aron, the patient who first inspired Muñoz more than a decade ago, has now become a cultural liaison to Hernández and two dozen other women from pregnancy into early motherhood.

“Childbirth is a spiritual energy event for the mother, the baby and the community,” Aron said.

She had hoped to deliver her daughter in the countryside with a traditional midwife. But Chilean law requires professional health workers to deliver babies because of past high maternal mortality.

So Aron turned to Osorno’s hospital and negotiated her delivery conditions with Muñoz, including being accompanied by a woman conversant in Mapuche practices and taking her placenta to bury ceremonially in her ancestral lands.

Mapuche people see the placenta as holding a twin spirit to the child’s. Its burial, often with a tree planted on top to grow as the newborn does, is believed to create a lifelong connection between children and the natural elements of their family’s territory.

“It’s something very poetic and very revolutionary,” said Alen Colipan, whose son’s placenta was placed by a river near his paternal grandmother’s house. “He will not feel this uprooting from his land.”

Colipan was 17 when she gave birth in Osorno’s intercultural delivery room, with a floor-to-ceiling photo across three walls of the rocky beach that is home to grandfather Huentellao, a protector spirit revered by the Mapuche Huilliche, the region’s Indigenous group.

Colipan said her then-85-year-old midwife, Irma Rohe, who had never entered a hospital, was allowed to receive the infant “without gloves and other imposed things” and ritually clean him.

“We’re going back to wanting to give birth with people with ancestral knowledge,” Colipan said. “Even our way of being born was dominated. We have to begin to liberate it.”

Chilean law now requires hospitals to give the placenta to mothers if requested. For a decade it has also mandated intercultural care in places with a significant Indigenous population. Mapuche people account for one-third of Osorno’s inhabitants and eight of 10 in the adjacent province of San Juan de la Costa, said Angélica Levicán, who has been in charge of Indigenous relations for the hospital since 2016.

“Health care among Indigenous people always existed. Then came another system to invalidate our own system,” she said. “Our intention is that they complement each other.”

To join both kinds of medicine is not easy. Many Indigenous people perceive public hospitals as yet another state institution that discriminates against their beliefs.

Mapuche medicine, based on spirituality, is also different from what doctors are trained for, said José Quidel Lincoleo, director of a center for Mapuche health care studies in Temuco, another southern city with a large Indigenous population.

Mapuche healers seek to connect with a patient’s spirit to discover the “biological, social, psychological and spiritual root of the problem” that is manifesting as a disease, Quidel added.

“It could be another previous life, or some harm done to you, or a lack of self-knowledge that makes us transgress on our worldview,” he said.

But doctors and traditional healers say they can complement one another’s work by realizing that every expert only knows a fraction of what’s possible, especially when battling new diseases like COVID-19.

“One understands that saving a body needs to be compatible with beliefs,” said Dr. Cristóbal Oyarzun, a rheumatologist and coordinator of internal medicine at Osorno’s hospital. “A patient with inner peace has better opportunities to heal.”

That’s hard to achieve in the aseptic, isolated environment of a hospital, especially during the pandemic. Mapuche healers continued to pray and “spiritually accompany” patients from afar, said Cristóbal Tremigual Lemui, a healer from San Juan de la Costa who has long collaborated with Osorno’s hospital.

“For us that is essential … so patients can receive the energy they need,” he said.

Family members also flocked to the hospital’s prayer space — an outdoor circle of small sacred laurel and cinnamon trees with a firepit next to the parking lot — to hold ceremonies for the dying, Levicán said.

Walk-ins and admitted patients who identify as Indigenous — an average of 50 a day — are welcomed and accompanied by Erica Inalef, the hospital’s intercultural facilitator, so that “they don’t feel so very alone.”

When, as a teen, she took her elderly father to a hospital, doctors would barely talk to them, and “body and spirit were separated.”

Now, doctors can see the enthusiasm with which patients welcome the arrival of consulting traditional healers, and that helps build mutual trust, Inalef said.

Trust can manifest in a traumatologist signing off on a patient’s lawenko — an herbal tea whose exact composition the healers hold secret — or in an obstetrician allowing a woman in labor to wear her munulongko, a headscarf believed to protect her.

Cultural clothing is one section in the labor plan Muñoz developed five years ago, which pregnant women can customize. She hopes more will become aware of this option — only about 20 of the hospital’s 1,500 births each year are intercultural deliveries.

“Indigenous women are doubly timid, discriminated against for being women, Indigenous, poor and rural,” Muñoz said. “We tell her, your body is the first territory you’re going to recover.”

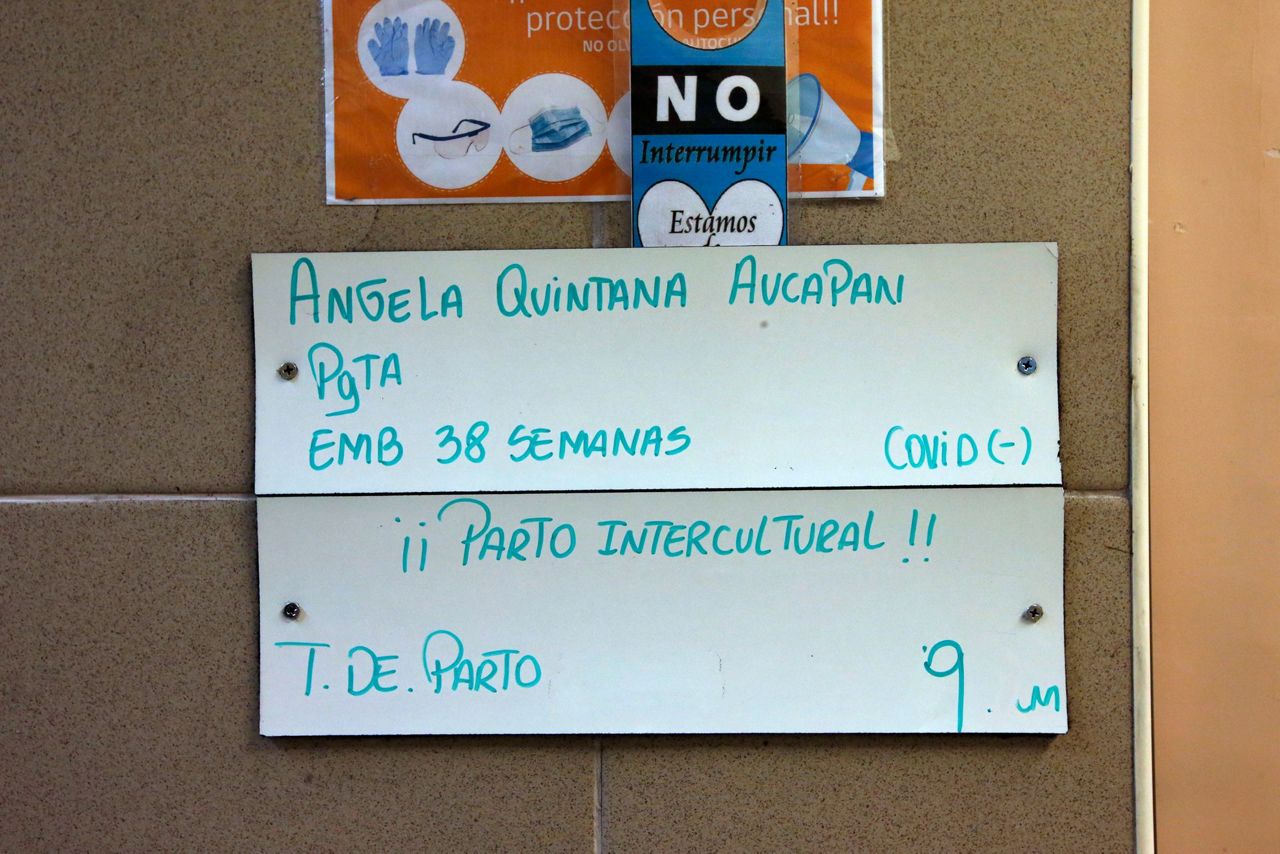

Reclaiming ancestral practices is what drew Angela Quintana Aucapan to have her baby — Namunküra, or “firm step” in Mapudungun — in the special delivery room recently, while relatives played traditional instruments.

“I was able to do it as my ancestors did,” she said. “With a ceremony while we waited for the new addition to the family, I felt supported as I received my baby.”

___

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

Copyright 2022 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.