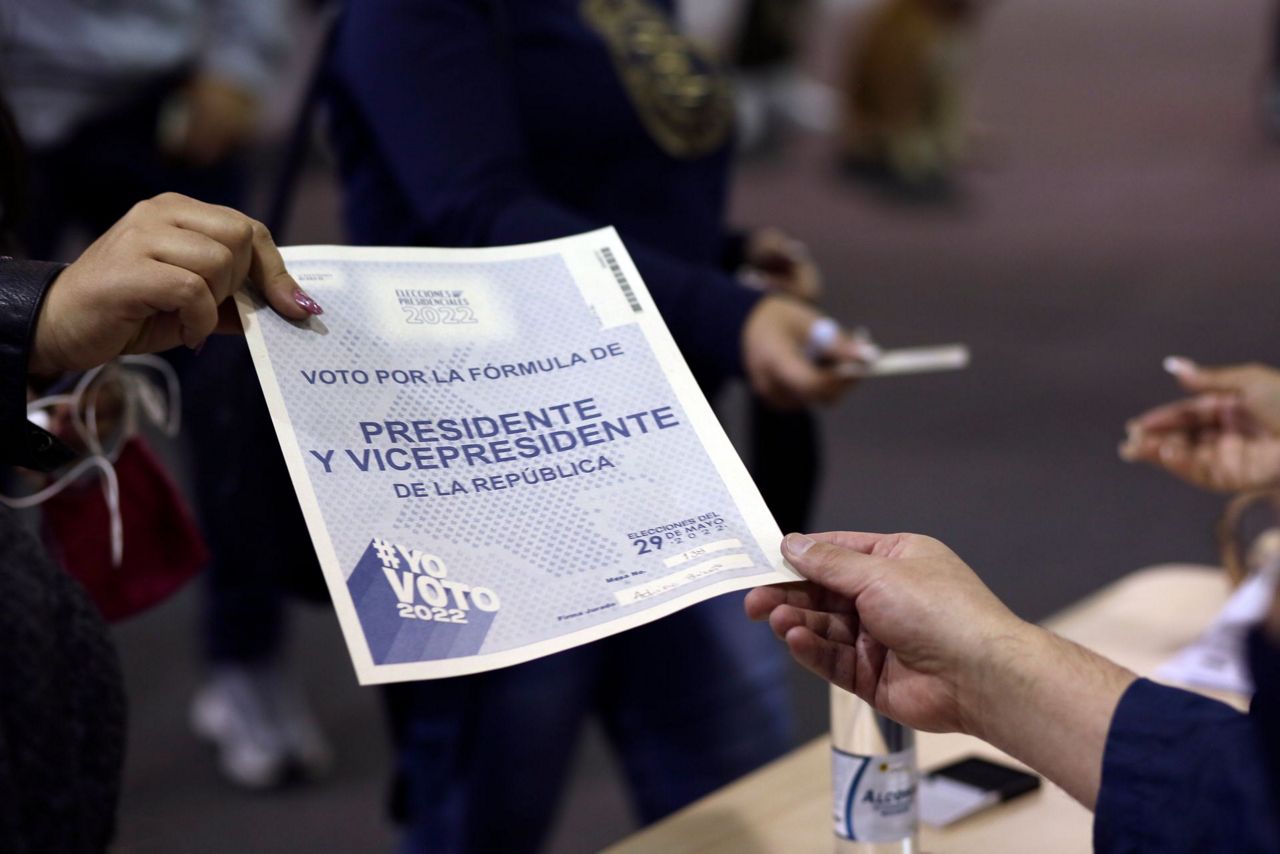

BOGOTA, Colombia (AP) — A leftist former rebel and a populist businessman took the top two spots among the six candidates in Colombia's presidential election Sunday and headed to a runoff showdown in June.

Leftist Sen. Gustavo Petro led the results with just over 40% of the votes, while independent real estate tycoon Rodolfo Hernández finished second with more than 28%, election authorities said Sunday evening. A candidate needed 50% of the total votes to win outright and the run-off election.

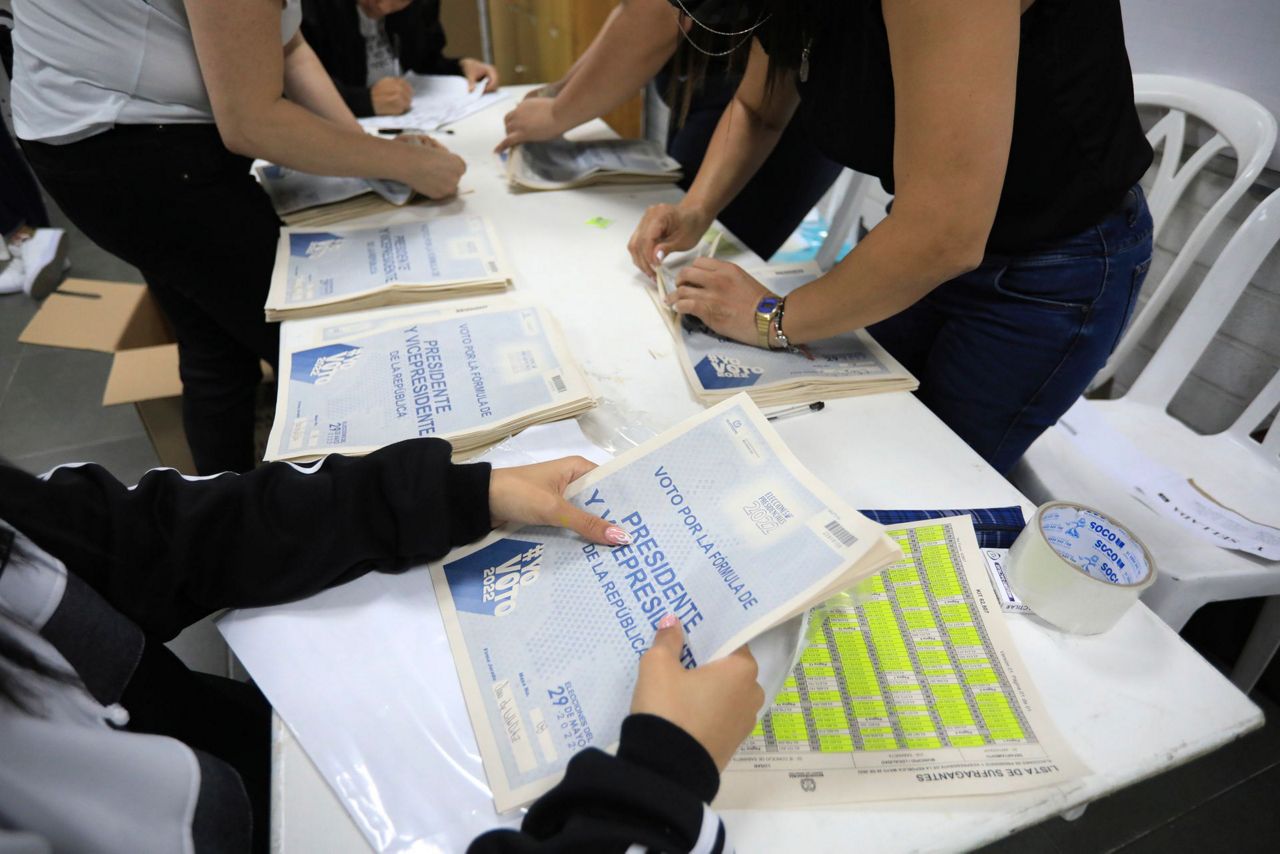

Voters in the South American country went to the polls amid a polarized environment and growing discontent over increasing inequality and inflation.

Petro has promised to make significant adjustments to the economy, including tax reform, and to change how Colombia fights drug cartels and other armed groups. Meanwhile, Hernández, whose spot in the runoff contest came as a suprise, has few connections to political parties and promises to reduce wasteful government spending and to offer rewards for people who report corrupt officials.

There has been a series of leftist political victories in Latin America as people seek change at a time of dissatisfaction with the economic situation. Chile, Peru and Honduras elected leftist presidents in 2021, and in Brazil, former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva is leading the polls for this year’s presidential election. Mexico elected a leftist president in 2018.

“The main problem in the country is the inequality of conditions, the work is not well paid,” said Jenny Bello, who sold coffee near a long line of voters under a typical cloudy sky in the capital of Bogotá. She had to resort to informal sales after months without work because of the pandemic.

This was the second presidential election held since the government signed in 2016 a peace agreement with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, known as FARC for its initials in Spanish. But the divisive agreement was not a main issue during the campaign, which focused on poverty, inflation and other challenges exacerbated by the pandemic.

Election Day took place peacefully for the most part across the country. But in the south-central state of Guaviare, three explosions were set off in rural areas far from polling stations, leaving a soldier with shrapnel wounds, said Defense Minister Diego Molano, who added that FARC dissident groups were allegedly responsible. The dissidents operate in the area.

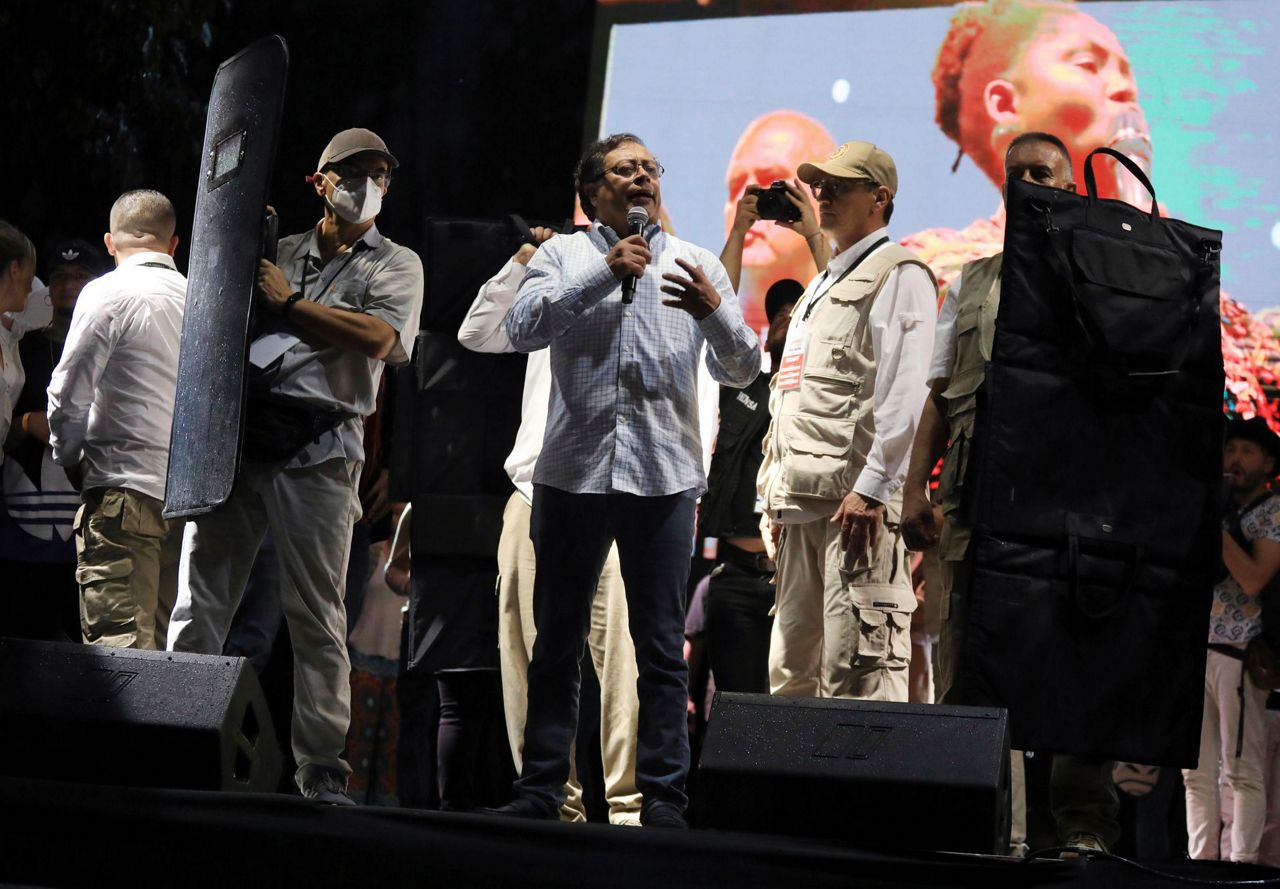

It is Petro's third attempt to be the South America’s country president. He was defeated in 2018 by Duque, who was not eligible for reelection.

A victory for Petro would usher in a new political era in a country that has always been governed by conservatives or moderates while marginalizing the left due to its perceived association with the nation’s armed conflict. He was once a rebel with the now-defunct M-19 movement and was granted amnesty after being jailed for his involvement with the group.

He has promised to make significant adjustments to the economy, including a tax reform, as well as changes to how Colombia fights drug cartels and other armed groups.

Petro's main rival for most of the campaign had been Federico Gutiérrez, a former mayor of Medellin backed by most of Colombia’s traditional parties who ran on a pro-business, economic growth platform.

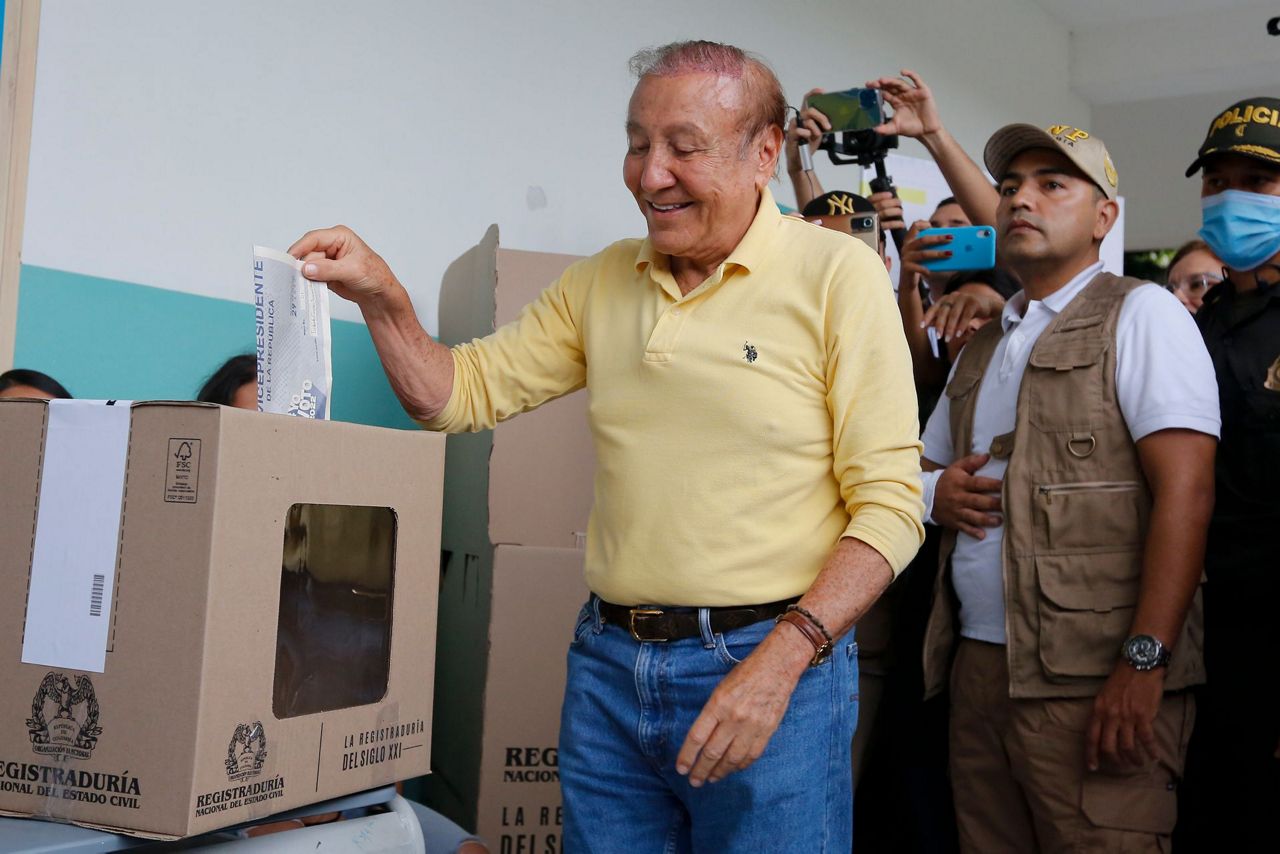

But Hernández, the former mayor of the north-central city of Bucaramanga, surged in recent polls with promises to “clean” the country of corruption and to donate his salary.

“Now, we enter the second period, and these next few days will be decisive in determining the future of the country,” Hernández said in a livestream after early results showed he advanced to the runoff. He said he remains firm on his commitment to end “corruption as a system of government.”

Historically, Colombia's early election results are consistent with the final count that authorities give days after the contest.

A Gallup poll conducted earlier this month showed that 75% of Colombians believe the country is heading in the wrong direction and only 27% approve of Duque. A poll last year by Gallup found 60% of those questioned were finding it hard to get by on their income.

The coronavirus pandemic set back the country’s anti-poverty efforts by at least a decade. Official figures showed that 39% of Colombia’s 51.6 million residents lived on less than $89 a month last year, which has a slight improvement from the 42.5% rate from 2020.

Meanwhile, the country’s inflation reached its highest levels in two decades last month. Duque’s administration has justified April’s 9.2% rate for April by saying it is part of a global inflationary phenomenon, but the argument has not tamed discontent over increasing food prices.

“The vote serves to change the country and I think that this responsibility falls a lot on young people who want to reach standards that allow us to have a decent life,” said Juan David González, 28, who voted for the second time in a presidential election.

In addition to economic challenges, Colombia’s next president will also have to face a complex security issue and corruption, which is a top concern of voters.

The Red Cross last year concluded Colombia reached its highest level of violence in the last five years. Although the peace agreement with the FARC has been implemented, the territories and drug-trafficking routes that it once controlled are in dispute between other armed groups such as the National Liberation Army, or ELN, a guerrilla founded in the 1960s, FARC dissidents and the Gulf Clan cartel.

Duque’s successor will have to decide whether to resume peace talks with the ELN, which he suspended in 2019 after an attack killed more than 20 people.

The other candidates on the ballot were Sergio Fajardo, former mayor of Medellín and candidate for the center coalition; Christian leader John Milton Rodríguez, and the conservative Enrique Gómez.

___

Garcia Cano reported from Caracas, Venezuela.

Copyright 2022 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.