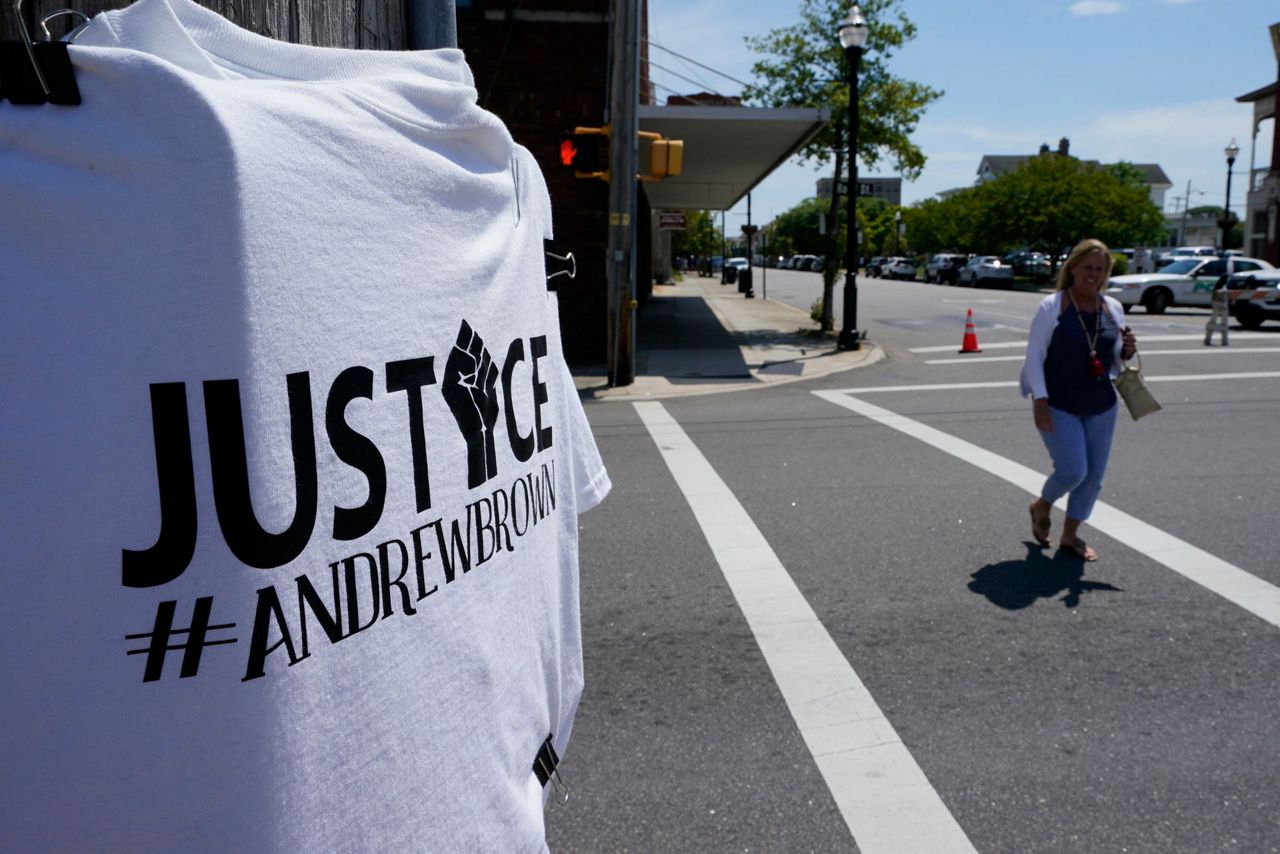

RALEIGH, N.C. (AP) — A North Carolina law that gives local courts authority over the release of body camera video has come under a harsh glare after a judge refused to make public footage of deputies shooting and killing Andrew Brown Jr.

The 2016 law says that law enforcement video is not a public record and generally cannot be released without court approval. A judge ruled Wednesday that body camera and dashboard footage of Brown's death must be kept from public view for at least another month to avoid harming a state investigation. The April 21 shooting happened as deputies were serving drug-related warrants at Brown's home in Elizabeth City.

Lawyers for Brown’s family and racial justice advocates decry what they see as slow movement to release video of his last moments. The family's legal team says the law stands in the way of transparency.

“This law makes absolutely no sense whatsoever,” attorney Bakari Sellers said.

Rules for access to body cameras vary by state and local jurisdictions. In Columbus, Ohio, police released body camera footage within hours of a fatal police shooting of a Black 16-year-old girl. That shooting happened the day before Brown, who was also Black, was killed.

A legal scholar who has studied the law says that it has received generally positive reviews from local governments.

“I’ve talked to cities and counties, and my sense is that the courts are handling it well,” said Frayda S. Bluestein, a law professor at the University of North Carolina’s School of Government in Chapel Hill. The Elizabeth City matter “is the first real sort of blow-up.”

Two North Carolina cases from last year show how application of the law can vary from place to place. Raleigh’s police chief asked a court in March 2020 to release footage of a nonfatal police shooting that sparked protests, and the footage was made public two days after the shooting.

In Forsyth County, a media coalition went to court in June 2020 to seek release of body camera footage surrounding the late 2019 death of an inmate. A judge heard oral arguments in July, and the videos were released a week later.

Chantal Stevens, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union of North Carolina, said the current law perpetuates a “racist system” by “placing unnecessary and sometimes insurmountable barriers between communities and the recordings that help them grapple with tragic circumstances.”

But Bluestein said having a judge decide on access appears to be better than leaving it to the law enforcement agencies captured on the footage.

“They’re not neutral. They have employees who might be at risk of being arrested,” Bluestein said. Outside groups and individuals can petition the court by filling out a one-page form available online. “It’s a bit of an extra step, but it seems to me it’s reasonable.”

Lawyer Mike Tadych, who represented a coalition of media including the Associated Press, said in court Wednesday that he’s worked on more than 30 requests to release law enforcement footage around the state since the law went into effect. Such video is often made public in two to three weeks.

Before the law went into effect, it was not always clear, in a legal sense, whether police footage was considered a public, personnel or investigative record, he said.

“The Legislature has set us at least somewhat straight in that regard,” he told the judge.

But some Democratic state lawmakers said this week that the current law isn’t good enough. They have filed bills that would ensure footage is released within 48 hours of a request, but the agency holding the video could ask a court for a delay.

“These bills build trust between civilians and law enforcement officials,” Democratic state Sen. Jay Chaudhuri said. “Releasing such footage in a timely manner reveals the truth. It serves justice when police misconduct occurs, and it protects law enforcement officials when they are falsely accused of misconduct.”

But a key Senate Republican said it was too early to consider the process broken based on the Brown investigation. When the law passed the Senate in a near-unanimous vote in 2016, the intent was to “to remove politics from the decision-making process and to forestall the possibility of a law enforcement agency refusing to release video,” Sen. Danny Britt of Robeson County said in a news release.

Republicans are open to considering improvements to the law, Britt said.

Rep. John Faircloth, a former police chief and sponsor of the law, said it was a good law when it was approved and still is so long as people in positions of authority use the process.

For instance, Faircloth said Wednesday in an interview, a mayor or city council seeking release of footage can ask their city attorney to petition the court.

“If they don’t, then it’s not the fault of the bill,” Faircloth said.

___

Drew reported from Durham, North Carolina.

Copyright 2021 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.