Ahmasi Lloyd never thought he would have to trade his home in Corona, Queens for a small rental in Woodside. The house had been in his family since 1952. Through inheritances, Lloyd and his siblings came to own it. But they owed $30,000 in property taxes and were struggling to pay their late sister's medical debts.

“And that’s when the knock at the door came,” Lloyd says. “He came with an offer for the house.”

It was a man from a company called the Jai Group, Lloyd says. The man told Lloyd his two brothers agreed to sell their two-thirds interest in the house. Now the Jai Group was coming after Lloyd's stake, too.

“He was ready to close the deal and I was the monkey wrench,” Lloyd says.

Turns out, the law was on the Jai Group's side.

When a property has multiple owners, generally any owner can force its sale by filing what's known as a "partition action" in court. The concept dates to English common law. But NY1 discovered, a growing number of investors are using partition actions to reap windfalls today.

“There is nothing to stop this sort of behavior,” says Scott Kohanowski, director of the Homeowner Stability Project with the City Bar Justice Center.

Kohanowski says Lloyd's case fits a pattern he has been seeing in the city recently: Investors swooping in, forcing the sale of houses that, through inheritances, are owned by many members of one family.

IS THIS HAPPENING TO ANYONE ELSE?

“I grew up in this house,” says Oakes.

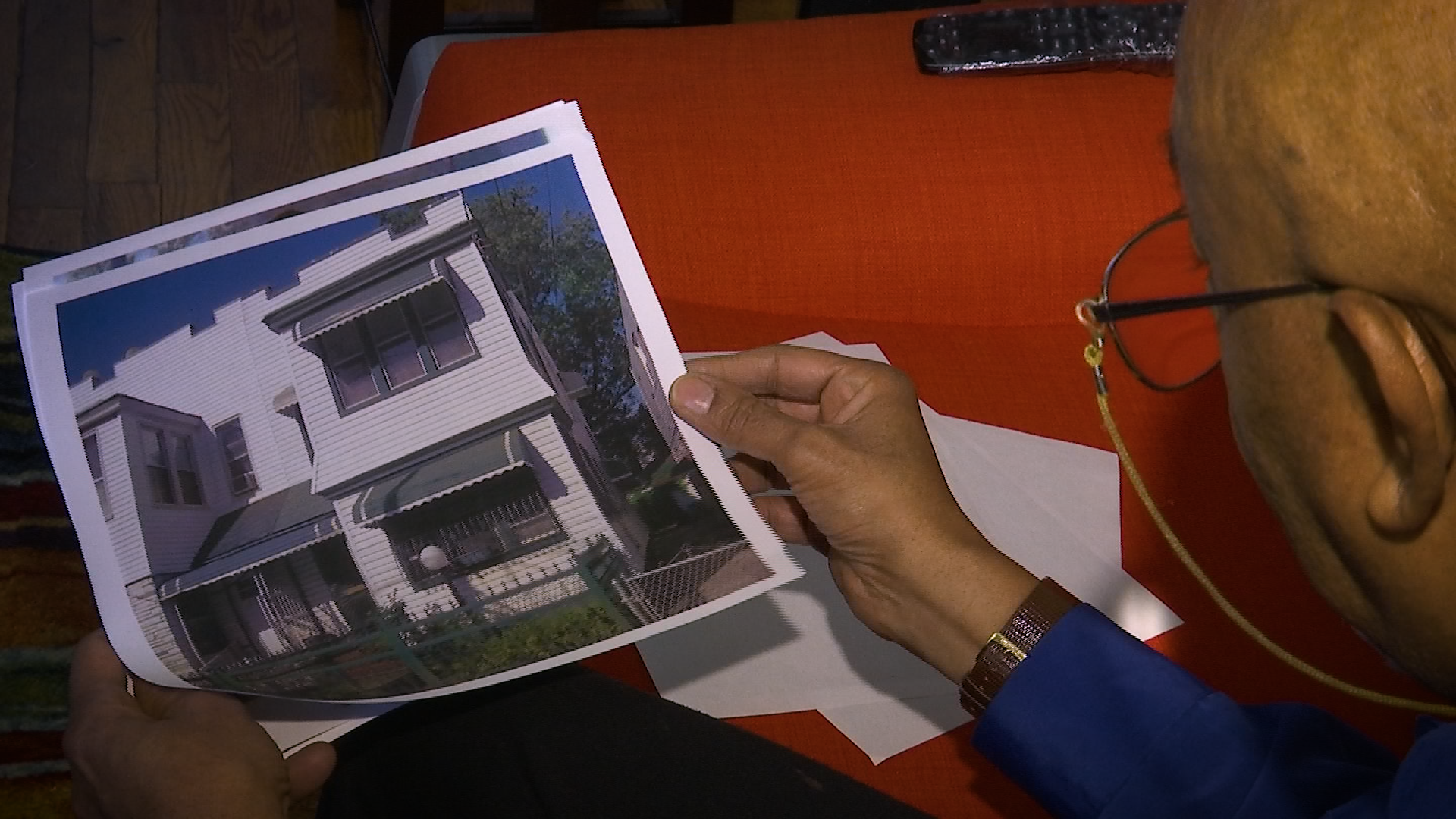

(Gail Oates pictured inside her home in Corona, Queens.)

She inherited eight percent of the property; 15 relatives inherited the rest. About two years ago, Oakes recalls, a man from the Jai Group appeared at the door, urging her to sell. His business card, according to Oakes, identified him as a “property investor.” Oakes says she refused his offer, but her relatives sold their 92 percent stake for $445,000.

“I was floored. I could not believe this,” Oakes says.

The Jai Group, which has offices in Uniondale, Long Island, declined to comment.

Oakes thought as long as she held out, she could stay in her home. But in December, the buyer of her relatives’ shares filed a partition action in Queens County Supreme Court.

The buyer, 3333 Group Corp., is based in Syosset, Long Island. It filed incorporation papers with the state in June 2018, shortly before it bought out Oakes’ relatives. The company did not respond to a request by NY1 for comment. Its precise relationship with the Jai Group could not be determined.

(Pictured above: Gail Oates's home in Corona, Queens.)

Oakes turned to Scott Kohanowski and the Homeowner Stability Project for help. Kohanowski says in two years, he’s helped six homeowners like Oakes and Lloyd.

“And you have to think, for every person that contacts us for help, there must be a dozen or more people out there that don’t,” Kohanowski adds.

NY1 found eight partition actions filed in Queens and Brooklyn last year against holdout homeowners.

Legal experts say in such cases, the holdouts often agree to sell because it's cheaper than fighting in court. And if there is no settlement, the court usually orders an auction. Either way, the home almost always sells for less than market value. Kohanowski fears that could happen to Oakes.

“If she doesn’t have sufficient money to find a new home, then she’s going to have to leave New York City entirely. And that just furthers this gentrification process that we’re experiencing,” Kohanowski says.

After his brothers sold their shares for $265,000, Ahamsi Lloyd decided to sell, too, for $135,000. The buyer also agreed to pay off the property taxes and the family’s medical debts, acquiring the house for a total of $525,000.

“It seems logical to think that if we had done it on our own, we probably could have made a little bit more change,” says Lloyd.

Indeed, five months after buying the home for $525,000 in 2017, the new owner flipped it - for $900,000.

“You’re kidding. Wow,” Lloyd said as he learned the about the sale for the first time. “That’s disconcerting.”

(Ahmasi Lloyd pictured holding a photograph of his childhood home in Corona, Queens.)

NY1 was unable to determine how much, if any, work was put into the house before it was flipped, but public records show no permits were issued for any improvements.

“[It’s] very upsetting because he had all these options he was deprived of,” Kohanowksi explains. He was exploring options to help Lloyd afford to keep the home, he says, before Lloyd’s brothers sold their interest in the property.

“He could have worked with his brothers,” Kohanowski says. “They could have put aside these disagreements that they had and come to an easy resolution and instead these investors stripped hundreds of thousands of dollars of accumulated wealth from him.”

WHAT CAN BE DONE TO PROTECT ONESELF FROM PARTITION ACTION?

- According to experts, someone with an interest in an heirs property who wishes to secure ownership should proactively identify all other owners in the property to discuss each owner’s plans for their respective interest in the property. Legal counsel during this process is suggested.

JH 3748 LLC, a limited liability corporation based in Manhasset, Long Island, is the entity that bought the property from Lloyd and his brothers, and then resold it. Records show it was created in May 2017, at about the same time Lloyd’s brothers sold their shares. The company was dissolved a year later. The company did not respond to a request by NY1 for comment.

For years, investors considered by some as predatory, have used partition actions to force sales of family farms at steep discounts. It's been a particular problem in the south, forcing the sale of farms owned for generations by African-American families. Experts say the relatively new focus on houses in New York is a result of gentrification, sending home values soaring in once-beaten-down areas.

“What we discovered was that in states throughout the country, especially in areas where the property value is rapidly appreciating, sometimes in gentrifying areas, sometimes in areas that for the first time really had gotten into the path of development, was that you had certain real estate investors or developers who then took advantage of partition law,” says Thomas Mitchell, professor at Texas A&M University School of Law, who has studied partition law for more than 20 years.

The problem, Mitchell says, is that holdout owners rarely get market value in court-ordered auctions. Instead, the auctions often end with the so-called predatory investor scooping up the property at a discount.

“The notice to the public that there will be a sale is scant, prospective bidders have no opportunity to inspect the property, so often times they have to assume it’s a lemon,” Mitchell says.

Mitchell leads an effort to help families facing the threat of partition actions. “We wanted to limit the abuse of these real estate investors, speculators,” he says.

“Often times, people who are living in these communities that we’re talking about are people who do not have asset portfolios that are very well diversified. Any wealth that they had as wealth is associated with their real property ownership,” he explained.

He was the principal drafter of the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act. It requires that judges favor dividing a property over selling it and consider who lives on the property and whether that person would become homeless in a forced sale.

“If one person has lived on the property for a long time, and has relied on it, we ought to be reluctant to have a sale that would dispossess that person from the property if there is a way of partitioning in kind and letting that person stay,” says Stewart Sterk, a professor Cardozo Law School.

But here in New York, a home like Oakes’ cannot be physically divided like a farm can, making a sale necessary. In states that have adopted the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act, forced sales must take place through brokers, on the open market, not at auction.

“It might deter speculation because they know they won’t end up with the property at a bargain price,” says Sterk.

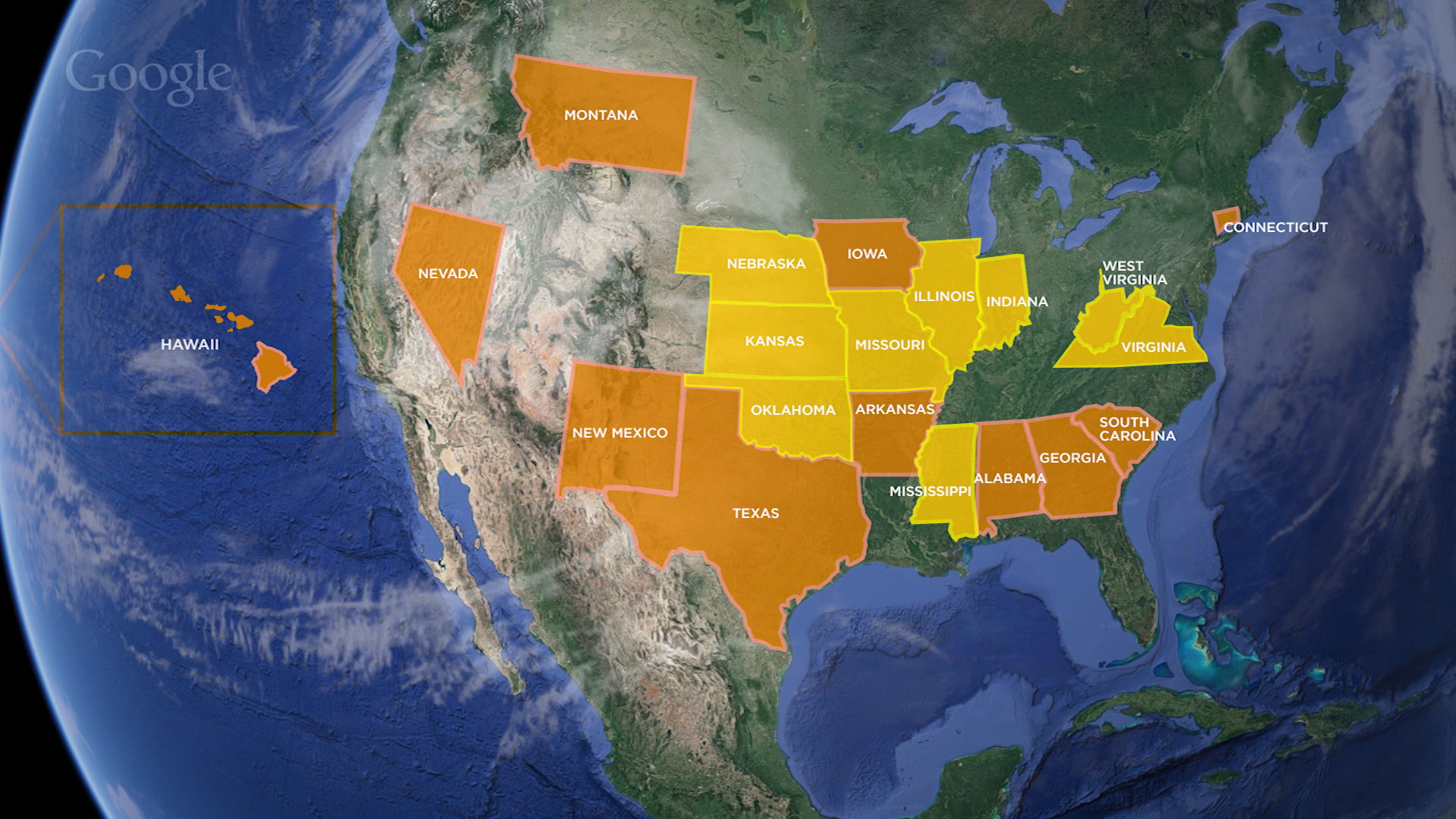

The uniform act has been adopted by 11 states and introduced in nine others, but not New York.

(Orange states: places where the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act has been adopted. Yellow states: places where the law has been introduced.)

Oakes and her legal team hope a legislator in Albany will take up the cause. If it is too late to help her, they say, perhaps a new law could save others from being stripped of equity that took generations to create.