New York soon marks a solemn anniversary: Hurricane Sandy, the worst natural disaster in the city's history. In Josh Robin's series, Sandy: Five Years Later, NY1 examines what has been done to better protect the five boroughs, as experts believe dangerous weather events will accelerate in this era of climate change and rising seas. We look at what the city has — and has not — done.

Nancy DiMauro is getting used to being back home.

"They're all working now," she said, testing the caps on her stove. "That one needs a cap — I lost the cap during the hurricane."

It's taken almost five years to rebuild after Hurricane Sandy sent floodwaters cascading into her house. DiMauro was finally able to return for good a few weeks ago.

She's not quite settled.

It's the same spot, but with the basement too vulnerable, her front door is more than five feet off the ground.

And one lock to a door, oddly, needs an extra tug since that late October day.

The storm drained between $25,000 to $30,000 of her savings. And as work began to elevate her home, she had a heart attack. Doctors say the stress made recovery more difficult.

And yet, an unusual feeling is returning: comfort. She's even sleeping well.

"I think is what affected me the most is not having a home, a place to call home," she said.

Like DiMauro, the city has come a long way from the devastation of Sandy.

But five years later, there is still so much to do.

The storm killed 44 people, the majority of them on Staten Island. It caused $19 billion in damage and lost economic activity.

From elevating streets in seaside communities, to storm-proofing the underground electric grid that powers the world's most famous business district, you can see evidence of the city’s recovery from Sandy and preparation for future storms.

But with hurricanes this year highlighting the risks facing coastal cities, New York may be moving far too slowly.

"Sea level rise rates are accelerating," said Philip Orton of Stevens Institute of Technology. "We're looking at somewhere between a foot-and-a-half and six feet by the end of this century."

"So dramatically worse in the long run," he added.

Over the past three months, NY1 has examined the city's rebuilding from Sandy and what is being done — and not done — to prevent similar devastation when the next storm arrives.

The city has spent more than $5 billion on Sandy-related recovery and resiliency projects, with $7 billion planned in the next four years.

The state is taking part in the recovery, too, forever changing Staten Island neighborhoods like Oakwood Beach.

As of Oct. 11 of 2017, according to New York State Homes and Community Renewal, 494 homes have been bought out, keeping it as open space. 23 more are expected.

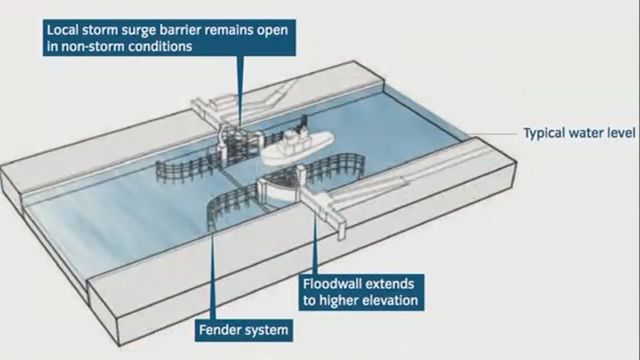

Con Edison lost power to more than 1 million customers. It's invested $1 billion hardening its network, including 3.3 miles of flood walls. It says 250,000 outages have been avoided so far.

Then, there's Build It Back. We've long heard complaints about the city-run program. By some measures, the pace is picking up.

But more homes are unfinished than done, five years after Sandy.

More than 20,000 New Yorkers were originally registered — the vast majority of which are single-family homes.

With many dropping out or ineligible, by mid-October 8,312 single-family properties remain. Construction has been completed on 4,111.

By elevating homes, the city is increasing the pace on making buildings more resilient. Officials say just under 7.7 million square-feet this year is better prepared versus 264,000 in 2016.

In public housing, Sandy affected 80,000 residents in more than 400 buildings.

The city's Housing Authority is spending a federal $3.3 billion grant to renovate and strengthen. Roof replacements are beginning at the Red Hook Houses.

But replacing boilers remains an obstacle: 41 temporary hot water boilers are still used at 16 housing developments, according to the New York City Housing Authority.

Just one development where Sandy took out a boiler has a permanent one back in place. For the rest, officials plan 2021.

Progress at schools is stronger. As of Oct. 12, 2017, 31 schools needed temporary boilers, while 29 now have permanent one.

And while repairs continue in some places, all 42 schools damaged in the storm are open for students.

We find a major gap in what public and private hospitals did after the storm. Sandbags line city-run Coney Island Hospital.

At private NYU Langone, there are automatic flood gates. It even has its own power plant.

The city has also failed to deliver what it proposed to prevent flooding in future storms.

After Sandy, then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg released more than 400 pages of plans and timetables.

There has been some progress, but major projects are scaled back and far behind schedule, such as in East Harlem, where a multi-million dollar flood barrier was supposed to have been completed by last year.

To critics, Mayor Bill de Blasio has also diluted a focused environmental plan. It was about protection in an era of rising seas. Now, it's grown to include social justice in an era of inequality.

"There are issues that are very, very important, and then there are issues that are existential in nature," said Seth Pinsky, who oversaw Mayor Bloomberg's resiliency plan. "I would argue that climate change is one of a very, very small handful of issues that are truly existential when it comes to the future of New York City."

"We face many challenges as a city," said NYC Chief Resilience Officer Daniel Zarrilli. "Yes, we face challenges from climate change, but as well as from increased inequality and other challenges."

"That has not reduced our focus on the challenges of climate change," Zarrilli continued.

The city says it's committed to the projects, with complexity responsible for new timetables.

Transit officials are also in the midst of a highly complex and disruptive rehabilitation.

Sandy unleashed more than $4.7 billion in damage to tracks, tunnels, and stations. Of more than a dozen crossings damaged during the storm, work has started or completed on all but the ones carrying the F and the L trains.

There are no dates set for repair on the F line, but the L train will largely be closed for 15 months, starting in 2019.

That closure is another example of how recovery from Sandy promises to change New Yorkers' lives long past this anniversary.

While Nancy DiMauro is finally moving back onto Staten Island, Jerry Wu recently moved out of Williamsburg.

"I moved about a month ago," he said. "One of the primary reasons for the move was actually because of the planned L train shutdown.

"It was going to be a tremendous disruption to my life."

We caught up with him recently in Brooklyn's Grand Army Plaza.

It's near his new home in Prospect Heights. He's getting to know the new neighborhood.